by Michael Olorunnisola

A Gentle Introduction to Data Structures: How Stacks Work

Anyone who’s applied for a developer job at a large tech company — and spent days practicing common algorithm interview questions — has probably concluded:

“Wow. I really gotta know data structures cold.”

What are data structures? And why are they so important? Wikipedia provides a succinct and accurate answer:

A data structure is a particular way of organizing data in a computer so that it can be used efficiently.

The key word here is efficiently, a word you’ll hear early and often as you analyze different data structures.

These structures provide scaffolding for data to be stored in ways that allow searches, inserts, removals, and updates to take place quickly and dynamically.

As powerful as computers are, they’re still just machines that require direction to accomplish any useful task (at least until general AI comes along). Until then, you have to give them the clearest, most efficient commands you can.

Now the same way you can build a home in 50 different ways, you can structure data in 50 different ways. Luckily for you, lots of really smart people have built great scaffolds that have stood the test of time. All you have to do is learn what they are, how they work, and how to best use them.

The following is a list of a few of the most common data structures. I’ll cover each of these individually in future articles — this one is focused 100% on stacks. Although there is often overlap, each of these structures has nuances that make them best suited for certain situations:

- Stacks

- Queues

- Linked Lists

- Sets

- Trees

- Graphs

- Hash Tables

You’ll also encounter variations on these data structures, such as doubly-linked lists, b-trees, and priority queues. But once you understand these core implementations, understanding these variations should be much easier.

So let’s begin part one of our data structures dive with an analysis of Stacks!

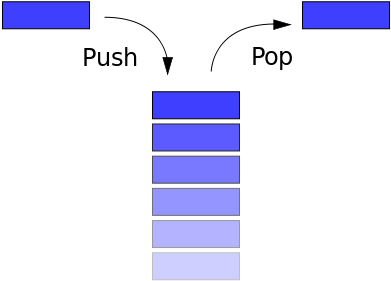

Stacks

- Literally a stack of data (like a stack of pancakes)

- Additions (push) — always add to the top of the stack

- Removals (pop) — always remove from the top of the stack

- Pattern type: Last item In is the First item Out (LIFO)

- Example use case: Using the back and forward buttons in your browser

In many programming languages, arrays have the functionality of a stack built in. But for the sake of being thorough, you’ll rebuild it here using a JavaScript object.

The first thing you need is to create a stack for you to store each site you visit, and a method on your stack to keep track of your current position:

class Stack { constructor(){ this._storage = {}; this._position = -1; // 0 indexed when we add items! } top(){ return this._position; }}let browserHistory = new Stack();Note that the underscore before the variable names signifies to other developers these variables are private, and shouldn’t be manipulated externally — only by the methods on the class. For example, I shouldn’t execute something like:

browserHistory._position = 2.This is why I created the top() method to return the current position of the stack.

In this example, each site you visit will be stored in your browserHistory stack. To help you keep track of where it is in the stack, you can use the position as the key for each website, then increment it on each new addition. I’ll do this via the push method:

class Stack { constructor(){ this._storage = {}; this._position = -1; } push(value){ this._position++; this._storage[this._position] = value } top(){ return this._position; }}let browserHistory = new Stack();browserHistory.push("google.com"); //navigating to MediumbrowserHistory.push("medium.com"); // navigating to Free Code CampbrowserHistory.push("freecodecamp.com"); // navigating to NetflixbrowserHistory.push("netflix.com"); // current siteAfter the above code is executed, your storage object will look a like this:

{ 0: “google.com” 1: “medium.com” 2: “freecodecamp.com” 3: “netflix.com”}So imagine you’re currently on Netflix, but feel guilty for not finishing that difficult recursion problem on Free Code Camp. You decide to hit the back button to go knock it out.

How is that action represented in your stack? With pop:

class Stack { constructor(){ this._storage = {}; this._position = -1; } push(value){ this._position++; this._storage[this._position] = value; } pop(){ if(this._position > -1){ let val = this._storage[this._position]; delete this._storage[this._position]; this._position--; return val; } } top(){ return this._position; }}let browserHistory = new Stack();browserHistory.push("google.com"); //navigating to MediumbrowserHistory.push("medium.com"); // navigating to Free Code CampbrowserHistory.push("freecodecamp.com"); // navigating to NetflixbrowserHistory.push("netflix.com"); //current sitebrowserHistory.pop(); //Returns netflix.com//Free Code Camp is now our current siteBy hitting the back button, you remove the most recent site added to your browser History and view the one on top of your stack. You also decrement the position variable so you have an accurate representation of where in the history you are. All of this should only occur if there’s actually something in your stack of course.

This looks good so far, but what’s the last piece that’s missing?

When you finish crushing the problem, you decide to reward yourself by going back to Netflix, by hitting the forward button. But where’s Netflix in your stack? You technically deleted it to save space, so you don’t have access to it anymore in your browserHistory.

Luckily, the pop function did return it, so maybe you can store it somewhere for later when you need it. How about in another stack!

You can create a “forward” stack to store each site that’s popped off of your browserHistory. So when you want to return to them, you just pop them off the forward stack, and push them back onto your browserHistory stack:

class Stack { constructor(){ this._storage = {}; this._position = -1; } push(value){ this._position++; this._storage[this._position] = value; } pop(){ if(this._position > -1){ let val = this._storage[this._position]; delete this._storage[this._position]; this._position--; return val; } }top(){ return this._position; }}let browserHistory = new Stack();let forward = new Stack() //Our new forward stack!browserHistory.push("google.com");browserHistory.push("medium.com");browserHistory.push("freecodecamp.com");browserHistory.push("netflix.com");//hit the back buttonforward.push(browserHistory.pop()); // forward stack holds Netflix// ...We crush the Free Code Camp problem here, then hit forward! browserHistory.push(forward.pop());//Netflix is now our current siteAnd there you go! You’ve used a data structure to re-implement basic browser back and forward navigation!

Now to be completely thorough, let’s say you went to a completely new site from Free Code Camp, like LeetCode to get more practice. You technically would still have Netflix in your forward stack, which really doesn’t make sense.

Luckily, you can implement a simple while loop to get rid of Netflix and any other sites quickly:

//When I manually navigate to a new site, make forward stack emptywhile(forward.top() > -1){ forward.pop();}Great! Now your navigation should work the way it’s supposed to.

Time for a quick recap. Stacks:

- Follow a Last In First Out (LIFO) pattern

- Have a push (add) and pop (remove) method that manage the contents of the stack

- Have a top property that allows us to track how large your stack is and the current top position.

At the end of each post in this series, I’ll do a brief time complexity analysis on the methods of each data structure to get some extra practice.

Here’s the code again:

push(value){ this._position++; this._storage[this._position] = value; } pop(){ if(this._position > -1){ let val = this._storage[this._position]; delete this._storage[this._position]; this._position--; return val; } } top(){ return this._position; }Push (addition) is O(1). Since you’ll always know the current position (thanks to your position variable), you don’t have to iterate to add an item.

Pop (removal) is O(1). No iteration is necessary for removal since you always have the current top position.

Top is O(1). The current position is always known.

There isn’t a native search method on stacks, but if you were to add one, what time complexity do you think it would be?

Find (search) would be O(n). You would technically have to iterate over your storage until you found the value you were looking for. This is essentially the indexOf method on Arrays.

Further reading

Wikipedia has an in-depth list of abstract data types.

I didn’t get a chance to get into the topic of a stack overflow, but if you’ve read my post on recursion you might have a good idea on why they occur. To beef up that knowledge, there is a great post about it on StackOverflow (see what I did there?)

In my next post, I’ll jump right into queues.