by David Valdman

Descartes, Berkeley and Functional Reactive Programming

Functional reactive programming is laden with unfamiliar terminology to the newcomer: pure functions, immutability, monads, etc. But beneath these concepts is a deeper principle — one debated long before Charles Babbage and the first computers. I argue the difference between object-oriented programming (OOP) and functional reactive programming (FRP) is as much about interpretations of reality as it is about structures of programs.

Here’s a thought experiment we’ve all likely heard:

If a tree falls in the middle of a forest, and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

There are many of ways to attack this question as ill-posed. Ignoring them for the moment, this question is poking at a fundamental aspect of reality: causality. Is existence dependent on, or independent of, observation? Let’s translate this thought experiment into code. Here’s a tree:

class Tree { constructor(){ this._fell = false; } set fell(state){ this._fell = state; } get fell(){ return this._fell; }} var tree = new Tree();tree.fell = true;To make the tree fall we set its fallen state to true. This is textbook object-oriented programming. Its patterns are getters, setters, and state. Simple enough, but in the context of our thought experiment there is a lurking interpretation: if one questions whether the tree fell, even if they didn’t observe it, the answer is a resounding “Yes!” One only needs to check that tree.fell is true. Those that answer yes to our philosophical question do so because they can return to the forest, see the fallen tree, and deduce it fell in the past. Here is the codified equivalent. Looks like we’ve solved that centuries-old riddle.

Not so fast! Let’s look at a different approach. Here’s another tree:

class Tree extends EventEmitter {}var tree = new Tree();tree.emit('fall');This is the “reactive” tree. Its patterns are events and transforms. In its purest form our tree maintains no state. We make it fall by broadcasting a fall event. Alas, the message falls on deaf ears! No state has changed, no evidence is left. There is no way to deduce the past by querying reality. Did the tree fall? *shrug*

Descartes and Berkeley

The object-oriented and reactive approaches give two different answers to our thought experiment because they embody two contradictory philosophies of epistemology: Rationalism, popularized by Descartes in the late 1600s, and Empiricism popularized by Berkeley in the early 1700s.

Descartes, in a streak of fanatical skepticism, found he could only be sure of one thing: his own existence. He came to this conclusion because he couldn’t doubt the existence of his thoughts and concluded there must be some entity doing the thinking, thus coining the phrase, cogito ergo sum: I think therefore I am. In other words: by acknowledging that there is some internal state that is changing, there must be some agent for whom the state belongs. To Descartes, changes of state is proof of existence — just like our first tree.

Soon after Descartes comes George Berkeley. Berkeley denounced the realist’s view. To Berkeley, it made no sense for material objects, like trees, to have existence. Existence only comes to us through thoughts (mental as opposed to physical experience), and thoughts must assimilate in the mind to exist. Material objects are deceptions; their essence is not their physicality but their ability to transform the immaterial. If a thought is not assimilated in the mind, it has no existence. Thus he popularized the Latin phrase esse percepi: to be is to be perceived.

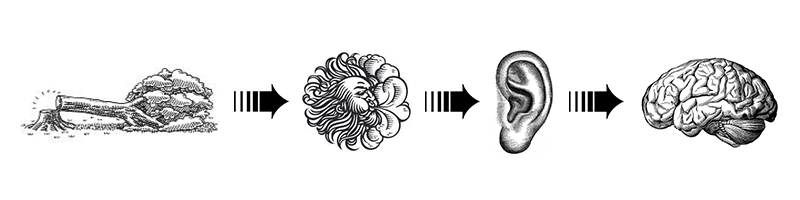

Let’s translate Berkeley’s reality into code. For our second tree to make a sound a mind must interpret it. We will create a chain of causality, starting from the tree falling, to the air vibrating, to the ear creating an electrical stimulus, to the brain interpreting it as sound.

When the tree falls, the air vibrates.

class Air extends EventEmitter { constructor (){ super(); function mapFall (fall){...} this.on('fall', (fall) => { var vibration = mapFall(fall); this.emit('vibrate', vibration); }; }}When the air vibrates, the ear converts it to an electrical stimulus.

class Ear extends EventEmitter { constructor (){ super(); function mapFrequency (frequency){...} this.on('vibrate', (frequency) => { var stimulus = mapFrequency(frequency); this.emit('stimulus', stimulus); }; }}When ear creates a stimulus, the brain interprets it as sound.

class Brain extends EventEmitter { constructor (){ super(); function mapStimulus (signal){...} this.on('stimulus', (signal) => { var sound = mapStimulus(signal); this.emit('sound', sound); }; }}We have effectively set up a chain of causality, which we make explicit by building a pipeline:

tree.pipe(air).pipe(ear).pipe(brain);Now, when the tree falls it makes an impression on a mind:

brain.on('sound', (sound) => { // We exit the system. You have been heard! console.log(sound); });tree.emit('fall', fallData);Berkeley called this concept Subjective Idealism. Idealism because it asserts only thoughts or ideas exist, and subjective because reality is dependent on the subjects that perceive it. In my opinion, Subjective Idealism is the philosophy underpinning reactive programming. Berkeley writes,

It is indeed an opinion strangely prevailing amongst men, that houses, mountains, rivers, and in a word all sensible objects have an existence natural or real, distinct from their being perceived by the understanding. …For what are the fore-mentioned objects but the things we perceive by sense…and is it not plainly repugnant that any one of these or any combination of them should exist unperceived?

I love this quote for its self-assured audacity. Berkeley is essentially calling us crazy for thinking that houses, mountains and rivers exist. In our example, trees, air, ears and brains are false idols; the only reality is mapFall, mapFrequency and mapStimulus. Reality is then never consumed, as it is with objects when they retain state. Reality is merely transformed.

Subjective Idealism in Practice

In OOP we create objects that encapsulate some kind of behavior. We then construct programs which are networked relationships of these objects. Our program is structurally a graph.

In FRP we create pipelines of functions that encapsulate causal relationships. Pipelines are then merged and branched to give the graph-like structure of an object-oriented program. However, there is an important limitation on the types of functions. Only pure functions are allowed. That is, functions that cannot effect anything outside themselves. In our example, the Ear object cannot change how the Air object vibrated. This constraint ensures that our pipelines have a well-defined direction from cause to effect. In terms of structure, this means our program is a directed acyclic graph (DAG).

To reason about software, we must think of it as a sequence of causal relationships. We must be able to order the program. Mathematically, a graph can be ordered if and only if it is a DAG. This is true no matter how you write your program. Whether you choose OOP, FRP or XYZ. What’s special about FRP, though, is that ordering is enforced by the pattern.

In OOP, ordering is left unspecified. Objects can call methods on other objects. Objects can change the state of other objects. Everything has read and write privileges by default. Specifying an order is done manually by the developer. It is up to them to relate the sequential ordering of lines in a program to an ordering of the objects’ causal relationships.

Unfortunately, this is all too easy to mess up. Notice that in OOP, when two objects write to the same shared state, you have a race condition. In FRP, when two functions try to affect one another you have an infinite loop. This is but one example of a theoretical pattern enforcing a practical result.

The bottom line is that it is not enough to encapsulate state. A well-written program will also encapsulate dependency.

Tradeoffs

“Programmers know the benefits of everything and the tradeoffs of nothing.”— Rich Hickey

You’d think after all this FRP praising and OOP bashing, I’d be firmly in the FRP camp. You’d be wrong! FRP is a programming pattern, and patterns serve to constrain solutions. If the ideal solution doesn’t satisfy the constraints, you’ll be wasting energy fighting against the pattern.

To be concrete, there are a few simple annoyances of FRP. Take immutability — you are always creating more memory. You can never, say, sort a list in place. You will always be creating a new list. In theory, immutability is a good pattern to observe. In practice, you may be memory constrained, and it may be a good idea to swim against the FRP current.

But this is not the glaring problem. The glaring problem is that FRP becomes an anti-pattern when you don’t know when two parts of a codebase will interact. Take, for example, a first person shooter game. Somewhere is a bullet object, and somewhere else is a player object. A bullet may hit a player, but it’s unclear when this will happen. These objects need to retain state (velocity of the bullet, health of the player, etc.) so it is available at the moment they interact. Perhaps in the abstract the entire game can be thought of as one causal pipeline, but that sounds more daunting to me than thinking in terms of decoupled objects and state.

To put on my philosophical hat once more, physics may decree that reality is one causal pipeline whose time evolution is governed by deterministic physical laws, and whose initial conditions (or probabilities) are provided by the big bang. But this is hardly how humans reason about cause and effect. We naturally slice up reality into higher-level objects and reason about their inter-relations. It can be simpler that way, even though it’s error prone!

I feel this is why FRP hasn’t been been wholly embraced by the programming community, even after seeing its many advantages. The best we should hope for when writing programs is to use FRP principles in places where its patterns fit the solution, and let them inspire OOP patterns where its patterns do not. To me this is a distinction between solutions that can be thought of as pipelines, and solutions that shouldn’t be.

Conclusion

In philosophy the objective is not to solve our deepest problems, but to have a shared language and historical precedent to debate them. So when a new problem emerges, we don’t have to start over. Similarly for programming patterns. They are not used to decide right and wrong, as if these concepts have universal appeal. They are used to classify problems and their approaches.

We should also look to other disciplines, much older than computer science, to see whether their shared language and historical precedent can inspire our own. Then we may see that the question, “did the tree fall?” is not answered with a yes or a no. That instead it questions a perspective. One that can frame our philosophy of epistemology or our architecture of programs. And one to which the answer lies between a state of mind, and a flow of thought!

Preview of Part II

There is still a nagging dilemma in our thought experiment. Even if there are no people to experience the sound, surely when the tree falls the air must vibrate! Right? In Part II we will go further down the rabbit hole to see that FRP can give a surprising interpretation here too. We’ll think of data flows in terms of push vs pull and see how this appears in concepts like lazy evaluation, algorithms like ray tracing, and applications like Excel.