by Ben Basche

Ghost in the machine: Snapchat isn’t mobile-first — it’s something else entirely

“Oh, you think darkness is your ally? You merely adopted the dark, I was born in it, molded by it.” — Bane

It’s tempting to think of Snapchat as a part of the app revolution, as one of the shining examples of mobile-first design that has defined our smartphone age.

This is of course true to an extent, but seeing Snapchat take its place at a consistent #1 or 2 in the US App Store alongside Facebook and Google’s main properties (and the other flavors of the week) somewhat obscures what is actually going on here.

Snapchat is not mobile-first, and it’s not really an app anymore. Nor is it a meta-app platform at this point like Facebook Messenger is angling to become (at least not yet). Snapchat is a true creature of mobile, a living, breathing embodiment of everything that our camera-enabled, networked pocket computer can possibly offer. And in its cooption of smartphones into a true social operating system, we see the inklings of what is beyond mobile.

When I open Snapchat up to the camera, I can’t shake the feeling that the ghost is banging on the glass, trying to break out into the world.

Mobile-first

As we come up on year 8 of of the app economy, it’s absolutely remarkable to think about just how far we’ve come. Mobile has completely reshaped old industries, created new ones, and turned the entire computing world on its head.

Companies from all sectors have met their end (or become shells of their former selves) for failing to think “mobile-first” — a term coined by Luke Wroblewski that has defined the age as much as “lean” and “design-thinking.” Most consumer-facing and many B2B verticals are being driven by companies that have designed or adapted their customer experiences to fit a smartphone dominated world.

And yet — like all great waves in technology — the ground shifts beneath the feet of even those who have aligned themselves around the dominant ethos.

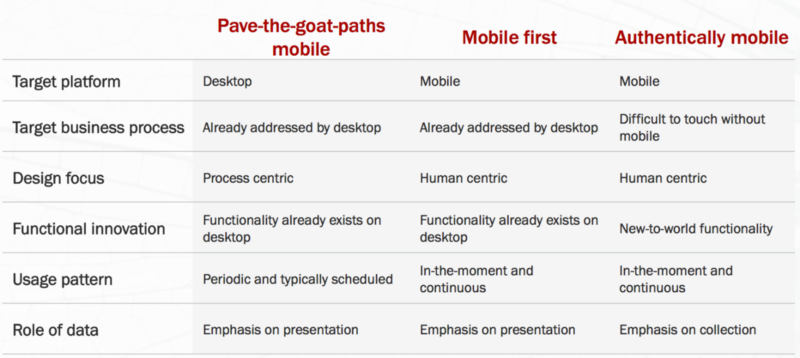

Peter Wagner and Martin Giles astutely wrote about these very rumblings last year in “Mobile First, But What’s Next?” They coined the term “authentically mobile” to distinguish services that not only are tailored for the mobile world, but who so thoroughly leverage the unique capabilities of mobile devices that they could literally not exist without them.

Where mobile-first companies take the new, portable form factor and riff on things that were more or less possible but limited in some way on the desktop, authentically mobile companies are truly creating experiences that would either be impossible or entirely meaningless without a networked supercomputer in our pockets.

A classic example of authentically mobile would be Uber, which without a location-enabled computing device always on our person (on both sides of the 2-sided marketplace), would almost certainly not exist. Wagner and Giles’ table here summarizes the shift:

It’s clear that Snapchat is extremely well described by column #3 — particularly with regard to its emphasis on collection — and if there were a column #4, it would be straddling the line. The “emphasis on collection” couldn’t describe Snapchat — an app which famously defaults to its camera — any more perfectly. CEO Evan Spiegel recently characterized Snapchat as primarily “a camera company.”

The Feed

No user-interface metaphor is as widely associated with the idea of “mobile first” design than the scrollable feed — whether it’s standard reverse chronology or algorithmically driven. One need only to observe people on public transit with their necks craned over their phones flicking up endlessly to feel just how pervasive feeds have become in our daily lives.

Outside of the big social players, the feed is found in countless other mobile apps ranging from productivity to personal finance. But although the smartphone form factor suits the feed incredibly well — from the focused screen size to the portability that has allowed content consumption to consume all the idle moments of our lives — it wasn’t born on mobile.

We began to see feeds everywhere towards the end of the desktop browser heyday, with the most important feed obviously being Facebook’s. In a way, Facebook made the browser wars irrelevant by essentially itself becoming the browser — the jumping off point for how we experienced the web. And despite intense skepticism from Wall Street, Facebook has been wildly successful in porting the News Feed over to mobile.

Adam Gale has a nice summary of just how handsomely this mobile bet has paid off for Facebook:

Indeed, Facebook (which includes WhatsApp and Instagram) is essentially a mobile company. Revenues on the platform jumped 70% year on year in the first quarter of 2016 (to $4.4bn, out of $5.4bn total revenues), having grown 82% the previous quarter. Mobile income now represents 82% of the business.

Just as Facebook was making this transition, and right when the iPhone’s camera gained the capability to take acceptable photos, a more pure, focused version of the Facebook News Feed emerged: Instagram. You post a few Instagram photos per week. Then you spend a lot of time scrolling through and looking at content, much like you would with the Facebook blue app. Instagram’s simple design, creative constraints and s̶u̶s̶p̶i̶c̶i̶o̶u̶s̶l̶y̶̶ consistently beautiful content make it a delightful mobile experience, and in many ways the crown jewel of Facebook’s attention empire.

Instagram is the pinnacle of Wagner & Giles’ “emphasis on presentation” hallmark of mobile-first. Instagram has long since eclipsed Facebook’s mindshare in the younger generation, and the acquisition has been hailed as one of the greatest in the history of technology. Facebook’s dominance over the feed metaphor is essentially complete and uncontested.

But we are beginning to see some cracks appear in both Facebook and Instagram. Earlier this year (ironically?) the Twittersphere was abuzz over a report in Bloomberg about sinking original (i.e. user generated) sharing on Facebook in what the company refers to internally as “context collapse.”

Anyone who has been on Facebook for long time probably didn’t need numbers to back up the general feeling that they and their friends weren’t posting big photo albums from the weekend’s events anymore, let alone sharing a cool song on someone else’s wall. VentureBeat reported around the same time that Instagram engagement had dropped a whopping 40% in 2015.

The Instagram numbers I take with a bit of a grain of salt as they don’t entirely pass the sniff test, but I think that while Instagram continues to grow (recently passed Twitter in a big way) and maintains a very privileged place in mediating our social hierarchies, people (especially young people) seem to be posting less frequently and are starting to spend their time elsewhere. It remains to be seen if Instagram’s algorithmic feed will fix this.

To be sure, Facebook and Instagram are still part of people’s hourly (ok — every 15 minutes) routine of “checking your phone,” but I don’t think anyone can deny that their apparent evolution into more passive consumption experiences doesn’t raise a few red flags.

Physics — back to the “now”

So what exactly is going on here? The numbers support the idea that Facebook and Instagram are wobbling a little in the US, and I think it’s reasonable to look at Snapchat’s continued explosive growth in users & engagement as one of the causes.

But why exactly are the two scions of the feed and the lynchpins of a mobile-first empire seemingly struggling to drive people to share their lives? Perhaps the task of constantly manicuring a persistent online identity — of carefully considering what effect your digital exhaust will have on your ego — is beginning to weigh on people. Both Facebook and Instagram are supposed to be arenas for the best version of yourself, and with each post you are putting something out into the ether to be judged both now and forever.

Mark Zuckerberg is famous for his extreme views on the singularity and persistence of our identity, going so far as to say that “having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity.” Consuming the feed exacerbates some of our darker insecurities which, in turn, put a ton of pressure on our contributions to it.

As everyone with a mom who made the family stop for a picture at every turn while on vacation can attest to, the urge to photograph all of the best moments of our lives is nothing new, but social media has turned this up to a fever pitch such that if it’s not posted, a moment might as well have not happened.

Before joining Snapchat as a researcher in 2013, Nathan Jurgenson wrote an essay called “Pics and It Didn’t Happen” that sheds some light on the chickens that are finally coming home to roost. He begins one of the most poignant sections here with a quote from Susan Sontag:

As Susan Sontag wrote in On Photography,

“there is something predatory in the act of taking a picture. To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed.”

Sontag notes that this makes for a nostalgic gaze, an understanding of the world as primarily documentable. For those who live with status updates, check-ins, likes, retweets, and ubiquitous photography, such an understanding is near inescapable. Social media have invited users to adopt a sort of documentary vision, through which the present is always apprehended as a potential past. This is most triumphantly exemplified by Instagram’s faux-vintage filters.

I don’t think it’s so much the simultaneous massaging and crushing of our egos that is weighing on the mobile-first giants of the feed. Snapchat Stories certainly have a component of performance and voyeurism that probably never goes away in social.

Rather, as we drown in an over-abundance of content destined for archive that has lost its meaning, the immediacy and intimacy of those platforms like Snapchat and plain old messaging have given us an island of engagement with the present moment.

Jurgenson absolutely nails it when he says “By being quick, the temporary photograph is a tiny protest against time.” In contrast, the feeds are crushing in their insistence that we are constantly living to relive the past.

The ghost in the machine — a sign of what’s to come

Countless people have observed (and often lamented) Snapchat’s “bad UX/UI” according to generally accepted design practices on mobile. Where “good design” calls for feature discoverability, Snapchat does almost no hand holding for new users and buries features behind complex gestures and unintuitively placed screens. From pressing on Discover stories to compose a snap to share + markup the content, to double filters (hold the first down and then keep swiping through), Snapchat is at once one of the simplest apps of its stature in the world and one of the hardest to learn.

Importantly though, it’s not really the UI that is the “hard” part about learning Snapchat (many have overstated the role of this feature bamboozling in keeping out “the olds”). Rather, the ambiguity around what Snapchat “is” and “what it’s for” is primarily responsible for the incredulity of onlookers and the so-called steep learning curve.

Beyond the visual design practices that have defined the smartphone era, perhaps an even more overarching principle that has guided the critique of mobile apps has been the idea of a core “problem” to be solved, a single organizing principle around which users can rally. Reminiscent of the early days of Twitter, Snapchat has faced questions about what it’s core use case is, but unlike Twitter which has arguably been consumed by this dilemma, Snapchat has embraced the ambiguity and essentially responded with ?.

Snapchat is very difficult to understand, even for those who use it regularly and think about it until their head hurts. The tangible reasons for its incredible success are numerous, overlapping and, at the end of the day, inadequate when compared to the actual feeling and experience of using it.

An interview Evan Spiegel gave to The Verge back in 2013 for the launch of Stories gives one of the best lenses (no pun intended) through which to understand what Snapchat is and what it was about to become. He said, describing the new feature:

When you have a minute in your day and are curious about what your friends are up to, you can jump into their experience. The last snap today will also be the beginning of tomorrow so there’s no pressure to compose a narrative. There’s this weird thing that happens when you contribute something to a static profile. You have to worry about how this new content fits in with your online persona that’s supposed to be you. It’s uncomfortable and unfortunate.

“Jumping into their experience,” I think is probably the closest thing I’ve heard to a unified theory of what Snapchat is. It connotes an active give and take between friends (and more recently, influencers). It foreshadows the importance of the doodles, stickers and filters that have come to define much of Snapchat, which are more about giving us an excuse to share anything — profound or mundane — than posing for an eternal self portrait. It’s something that only really works when the capture and consumption device are the same, and where the output — vertical photos/videos — fully immerses you in each experience shared with you.

And like all real experiences, these shared “jumpings” are fleeting. We can put a different persona on (with face filters, now literally) each moment and be reborn the next. Snapchat itself feels like it’s constantly pulsing like one of those time lapse videos of cars and city lights. We all go “there” when we get a peek into each other’s lives, but really there’s no there, there.

In this way, Snapchat the “place” is everywhere and nowhere at the same time. The “app” lives as much in our own mind and habits— the latent potential of any moment to be instantly shared, experienced together, and forgotten — as it does on Snapchat’s servers. Rather than looking at the inherent ephemerality of life as a bug like some of its competitors, Snapchat sees it unequivocally as a feature. Without this impermanence, Snapchat would feel like surveillance. Instead, it feels more like teleportation — somehow allowing us to be together when we’re apart.

It’s no surprise that even as Snapchat remains a fraction of Facebook’s size, it has nearly caught the blue giant in terms of photos shared daily. Ben Thompson had a great piece where he posited that tech markets all seem to have a “phonebook” and a “phone” — the phonebook being the grand directory of both people and content, and the phone as the go-to place for actively connecting with the most important people in our lives. In the US, he stated the obvious: Facebook is the phonebook, and Snapchat is increasingly becoming the phone.

This might appear to be a stable stalemate, but I pose the question in light of Facebook’s frantic attempts to get Messenger to catch on in the US: how long can the phonebook live without the phone? Much like Facebook became the browser on the desktop and took its momentum into the mobile-first world, I think we should expect authentically mobile Snapchat to parlay its takeover of the phone into whatever comes next.

Update 6/30: Two interesting new stories I felt I should include here as an addendum