by Jed Watson

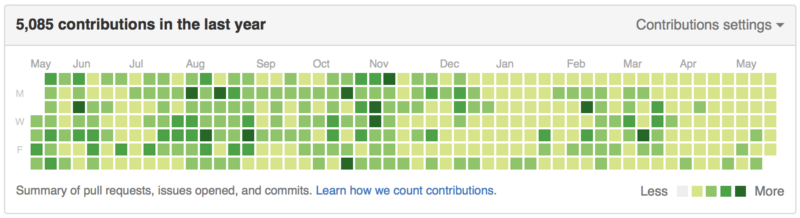

GitHub broke my 1,000 day streak

… and this is what I learned about myself, and open source, along the way.

I was always planning to write a post when I broke my contribution streak. My first child (a beautiful baby girl we named Grace) was born five weeks ago, and I honestly didn’t think my “commit some code every day” habit would last through that experience, or even leading up to it.

Well, my habit did last. And this in no way reflects how present I was as a new parent, nor my ability to sort out my own priorities like a proper adult. Unlike some streak criticism, mine was personal and not for show or fame and wasn’t a sign of a distressed work/life balance.

Then again, when I started I didn’t think it would last about a thousand days — yet that’s roughly how long it has been (how long for sure? GitHub won’t tell you anymore, but based on my math it’s about 980 days)

Ultimately, all streaks will be broken, and like many long-lived ones, I guess I’ve been wondering why and how to end it. Out-lasting the feature on GitHub then — the one that inspired me to start it in the first place — seems like a fitting way to go out.

This is my story, more because I want to tell it, than because I think you (or anyone) should read it. It’s been a personal journey played out in a public space, and so this seems like a fitting way to wrap it up.

Warning: this is a bit rambly. It’s a snapshot in time of someone who’s just worked at something for nearly three years and seen it disappear. The number isn’t important, and the publicity less so. But it’s been a constructive motivation in my life that I deliberately opted into, and I’m feeling pretty introspective and processing a lot now that the whole thing is done.

My streak started in September 15th, 2013. I had returned from a five week honeymoon around Europe with my wife in July, and was ready to start a new life; by coincidence, that was also the day my company Thinkmill was officially registered. So, two birthdays in one.

But it was probably two weeks later when I consciously decided to keep it up; like a personal challenge. I had also recently open sourced KeystoneJS which was one of the scariest moments in my life (what if people hate it! what if I get judged? what if I’m not good enough?)

… which lasted all of a few days until I realized nobody had noticed. Nobody cared, and nobody knew who I was. Heh. It’s not actually that scary. Turns out if you want somebody to pay any attention to your open source stuff, you have to work for it.

So the streak started as a public way to say “Hey! I’m committed to this! You can trust my scrappy little open source project because I’m obviously paying attention to it and dedicated to building it!”

I went about two weeks before I knew I’d have to tell my wife; if I didn’t have her buy-in, there was no way it was going to hold up. So I did, expecting her to dismiss it; instead, she got that I was doing something different and important to me, and encouraged me instead. I thought I’d go for a few months maybe, if I was strong.

A few months in, my initial motivation of “something to prove” had disappeared and two patterns emerged instead:

- It got hard. There were days when I didn’t want to keep it up. I wanted to tap out and let it go. Hardest of all was when I was under the gun at work and already pulling 12 hour days on things that didn’t count. But I’d come so far; just do something. So I did, and invariably a day or two later I would be past it, and things were easy again. Lesson #1

- I realised that when I didn’t have time to fix something big, I’d pick off an easy issue from the pile (turned out people did like Keystone, and the natural result of this is GitHub Issues) and fix it. I was addressing things users cared about, and the quality of my project was better for it. This “good maintainer” thing led to more interest, more engaged users, and eventually some amazing contributors / collaborators. Lesson #2.

Buoyed by this, I was feeling really good about the streak. I was also refining my art. I love coding, even though I often get caught up with business / management / architectural concerns, and no matter what else I do, coding is my art. Dedicating time to it every day (#1) and collaborating with an ever-expanding community (#2) are the best things I’ve ever done to develop my skill and experience.

April the next year, my wife and I went on holiday to China for a couple of weeks. I was sure this was the End Of The Streak. Because I’m not going to let it be my life! It’s not healthy. Plus, there’s no way my wife would have patience for me coding on holiday :)

… but I was wrong. Initially, because I checked my notifications at the airport and merged a really good looking PR (being responsive to contributors is really important, more on this later!)

Then I fixed a simple bug. It had momentum, and was so easy to keep up.

About halfway through my wife asked “have you done your streak yet?” and I told her “no, I’m not worrying about that”. She insisted. She’d seen the positive impact it had on me, and encouraged me to continue. For all the months I’d benefit from it after we’d come back, it was worth 15 minutes a day for the next week. I’d worked so hard for it, she said, don’t throw it away now.

“Have you done your streak yet” became a common refrain in our house over the next couple of years, always with encouragement and never resignation.

If things are good for you, the people who love you will notice and encourage them. Lesson #3

Having an unbroken streak of nearly a year seemed a bit crazy. One of my friends went on his own self-driven coding adventure (Hi Tom ?) and made up a status dashboard on a big TV in our office, Panic-style, and one of the modules on it was my streak, in an industrial “days since last accident” design. It was fun, and egged me on a bit.

Turns out being disciplined can be social and fun. Lesson #4

Worth noting, though, at this point my life was set up around what I now recognized as a discipline. It wasn’t always easy, but no discipline is, and I worked at it. Having the support of my friends and family was crucial, and running a business where we were able to construct a healthy relationship between commercial and open source work was also extremely important.

If you’re going to do something hard, be smart about it, and set it up to be sustainable. Lesson #5

The next year was a bit of a blur. Keystone grew, but I was always humbled when people had heard of it, or liked it. Through this, what developed strongly was a sense of “building something for good”. I’m not giving my time to work for free, I’ve just got these ideas to express (in the form of software) that I think will create benefit beyond what I could achieve on my own or for myself.

I feel like I’m pretty blessed in life. Some would call it privilege, luck, fortune, whatever. I’m OK with that, because while I can’t repay everyone who’s ever helped me I can pay it forward and be as generous as possible with time, code or advice.

But you know what? it comes back. At the start of 2015 I had the opportunity to go to the first React Conf where I made some excellent friends and started being part of the React Community. By this point, maintaining my streak was pretty much second nature. Almost forgotten, but still a discipline held, and foundational to the way I behave.

One of the absolute highlights of 2015 was traveling to Paris for React Europe to talk about React and Mobile Apps. But not just for the conference or the talk. That year I’d become friends with Camille Reynders, a KeystoneJS team member, over many hours spent talking on Slack and working together. But we’d never met, because he lived in Belgium while I’m in Sydney.

He and his wife drove down to hang out that weekend, just to spend some time in real life. We sat in cafes on the streets of Paris, watching the Pride Parade go past, eating cheese, drinking beer and hanging out.

Starting an Open Source project and dedicating yourself to it can get you some great friends and unique experiences. Lesson #6

Coming into 2016, my wife and I were expecting our first child. I had a frantic start to the year, running a growing business and traveling overseas nearly monthly getting things done before I went seriously into family mode for a while.

There was Nodevember — my first major conference talk on KeystoneJS, in Nashville. Then PhoneGap Day US in Utah where I pitched React to what felt like a room full of Angular developers. Then React Conf 2016 in San Francisco in February. At this point, each trip felt like catching up with friends, learning new things and developing ideas with developers I admire and am just flat-out stoked to spend time with in person.

To contrast with my first experience open sourcing KeystoneJS to crickets, I’ve now got packages on npm that get over a million downloads a month, thousands of followers, and something like 15,000 stars across my various personal projects.

But more importantly I’ve been told by several people that I’ve inspired them to get into open source as well. That’s not a small thing, and something I’m really proud of. Because I believe contributing to open source is personal, powerful, and good.

These days, it’s not uncommon for me to hear feedback that the community around KeystoneJS is supportive, inclusive and inspiring. There are now other people inspiring yet more people around something that I created and imbued with my personal energy and philosophy, and that is just awesome. No other word for it. That is why I do this.

Not to mention all the thanks, credit, and opportunities that have come flooding back in return. I do this for me, because I believe in this way of creating value, but having that realized with feedback is powerfully helpful.

It’s frankly been a lot of work, and sacrifice. But also? Totally worth it.

Now, while I’ve taken personal and private pride in my streak and various other metrics, it’s worth making some points.

This is personal. It’s been good for me. It’s not for everyone. There is no judgement if you benefit from a more clear-cut work/life balance. I have no argument to make against those who say the GitHub streak guilts them into working on weekends and they want it gone.

There are also downsides to open source that I didn’t understand when I started. Guilt is massive and real. When someone submits a PR and I sit on it, I feel terrible for ignoring (or even just apparently ignoring) their work. Their time is valuable and they gave me some of it; in balance, they’re implicitly asking for more of mine to review and maintain their suggestion.

Sometimes I’m a great maintainer, and respond quickly with helpful feedback or just a “Merge PR” click. Other times, I’m not. I’ve been lucky to have people help me out as well, with vetting, triaging and taking on maintenance roles in various projects. I can’t thank those people enough.

This morning when I woke up and found out my streak had been removed, it just felt… weird. Not like I was robbed of something, not like I was liberated either. Just a bit empty, a bit numb. All those time I’d thought about it and been encouraged not to, and the choice was taken away from me. How anticlimactic.

I don’t know if the campaign to remove streaks from GitHub’s UI was something I really agree with. I get the arguments, especially from a mental health perspective. Just because I can look back and feel good about my experience, maybe on balance I was an exception. Maybe for every developer who was constructively motivated by it, there was another who was unhealthily punished by it. Addressing health and balance in our (and every) industry is a positive thing, along with equality and inclusion.

Clearly it’s been good for some people. John Dalton’s been on a streak longer than mine and is one of the most inspiring developers I know. John Resig, I think, motivated a great number of developers with his “Write Code Every Day” post. As he said:

I consider this change in habit to be a massive success and hope to continue it for as long as I can. In the meantime I’ll do all that I can to recommend this tactic to others who wish to get substantial side project work done.

Having kept it up for nearly a thousand days, I’m OK to stop streak-counting. Maybe I’ll keep that graph all green, or maybe some grey will sneak in. It doesn’t really matter; after three years, the discipline has done its work, and I’ll be the beneficiary of it for the rest of my life. And hey, I was planning to break it sometime anyway.

I do wonder, when mechanisms for self discipline and motivation can cut both ways, and then be unilaterally removed (I assume in response to a vocal movement) what the next thing will be for a generation of developers who are just getting started? We humans respond well to pressure, competition and games. It’s the very instinct that made the streak such a powerful metric in the first place.

I hope something new emerges that doesn’t have such a negative downside (the rock → hard place text was always a bit caustic) yet inspires developers to challenge themselves the way the GitHub Streak did.