by Sanchit Gera

How I learned to love Vim

I’ve had a bitter-sweet relationship with Vim for a long time.

Over the last couple of years, I tried to learn Vim on several occasions. Each time, I ended up abandoning it. Instead, I would resort to my ‘primary’ text editor (usually Atom).

But for a couple of weeks, I found myself unable to use Atom. This was due to an obscure connectivity issue. This made my setup completely useless over remote connections.

After going through the five stages of grief, I decided to bite the bullet and try (again) to learn Vim. This time I forced myself to use Vim, and Vim alone.

I know — I could have easily switched to a more intuitive editor such as Sublime. Or I could even have used a fully fledged IDE like IntelliJ.

Instead, I figured “what the hell”. Here are some of the things I learnt.

Learning the basics

In case it’s new to you, Vim is a seemingly archaic text editor. Its roots go back to a program call Vi, which appeared during the 1970s.

Part of Vim’s appeal — and annoyance — is due to the fact it is designed to work entirely with your keyboard. After all, point-and-click GUIs weren’t really a thing back when Vi was conceived.

Vim instead uses modes. There are two main modes that can be used:

- Normal mode: this is the mode you use when you are navigating your files, or editing/manipulating them. This is mode for doing anything that does not involve typing new content. Most Vim commands are entered while in this mode.

- Insert mode: insert mode allows the input of new text. In this mode, Vim behaves more like a ‘normal’ text editor, such as Atom or Sublime. Minus the use of a mouse, of course.

Other modes exist in Vim too. One example is the visual mode, for selecting large chunks of text. Typically, these modes are used much less frequently.

Vim is normally used inside a Terminal emulator. However, standalone distributions exist. It is available on virtually all Unix and Linux systems. Vim’s grandfather, Vi, is part of the UNIX specification. It therefore comes preinstalled on all conforming systems.

Composability

‘Composability’ is largely what makes Vim different to other editors. It gives Vim its own special language.

It introduces the notion of nouns and verbs in the context of text editing and manipulation.

Verbs describe actions that you can take (such as delete, change, move).

Nouns describe what is being acted upon (usually words, lines or places within the text).

Some of the nouns/verbs commonly used include:

Verbs d: deletec: change (overwrite)y: yank (copy)>: indent<: unindentActionsh,j,k,l: left, down, up, rightw: next wordb: previous word0: start of line$: end of linei: inside (excluding the following character)a: around (including the encasing characters)This list is non-exhaustive. There are tons and tons of key-bindings available. But you can achieve a lot with only the very basic ones. The idea is to chain together combinations of nouns, verbs and occasionally numbers. This allows you to create distinct actions to manipulate the text as needed.

For example, to delete a word you type in the key combination dw.

To delete 2 words from the current position, you type in d2w.

To delete from the current position all the way to the end of the line, you type in d$.

To delete everything inside a pair of parentheses, you would type di(. And on it goes.

This method of working might not seem worth the hassle. But if you force yourself to use the combinations every day, they will become second nature. After a certain point, the speed you gain by reducing the number of keystrokes required to make a certain edit is absolutely thrilling. More on that next.

Vim is addictive

Yes, I know. It’s a cliché. But bear with me.

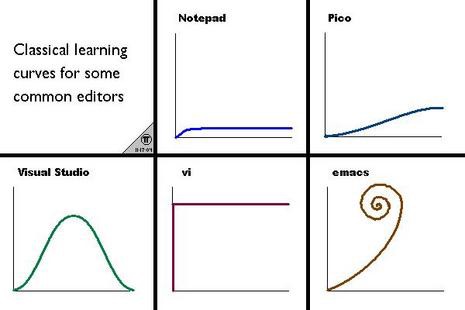

Vim has a notorious learning curve. But once you get past the stage where you are constantly cursing your computer screen, using Vim is actually quite fun.

Learning to use Vim’s cryptic commands lets you fly through the file editing process. After a while, it almost feels wrong to lift your fingers away from the home row on the keyboard, or even to use the mouse!

After only one month, I find myself missing Vim’s navigation system and other shortcuts while using my computer regularly.

In fact, at one point I considered experimenting with this extension to enable Vim keybindings while browsing the web. I know!

Fortunately, the programming community recognizes this. Most mainstream text editors have some way of enabling Vim keybindings. This puts ‘Vimmers’ out of their misery by giving them the best of both worlds.

Giving Vim a fighting chance

The key improving at Vim is to simply not use anything else. Instead, you should force yourself to do everything the Vim way.

For example — when editing files in Vim, try not to resort to your old habits. Most people, when starting out, try to stay as far away from ‘normal mode’ as possible.

Instead, they try to spend as much time as they can in ‘insert mode’. In this mode, it is easy to feel more at home. It lets you get away with editing your file without learning anything new. But this is a mistake.

If you are genuinely interested in learning how to make Vim work for you, you have to put in some effort. This means taking the time to figure out the ‘right’ way to do something.

If you find yourself repeating keystrokes over and over again to achieve any task, stop. It is likely there is a better way to do what you are trying to do.

Google it. Memorize it. Add it to your arsenal. It is far easier to learn new commands this way, compared to reading a list of commands and hoping you’ll need to use one of them.

After a couple of days, you may develop an intuitive sense of when you are wasting keystrokes. Heed to your intuition.

Appreciate (?) modern editors

Another big reason many people shy away from Vim is the seemingly ‘barebones’ nature of it all.

By default, Vim comes with no plugins or nice-to-have features. And what Vim considers to be a ‘nice-to-have’ feature is probably very different to what programmers used to modern IDEs would consider ‘nice-to-have’.

Vim comes with barebones syntax highlighting (which is disabled by default). There is no line-numbering (again, this needs to be enabled separately).

No surprise, then, that things such as:

- default Git integration

- ‘complete-as-you-go’ code completion

- automatic bracket completion

- code snippets

- custom color schemes

…do not come pre-installed with Vim.

This might seem like huge turn off — especially for programmers used to developing in powerful IDEs that do a lot of heavy lifting. Many come installed with a whole bunch of plugins and extensions designed specifically to make your workflow more efficient.

And there is some merit to this argument. Vim has its limitations.

Yet on the flip-side — even though you appreciate what modern IDEs provide and the work that goes into building them — you also realize that most IDEs (and even modest editors such as Atom) bring with them a lot of bloat.

Advanced IDEs come jam-packed with features that are hardly used by average users.

Learning to use Vim effectively is partly an exercise in working out which plugins are absolutely critical to your productivity. The key is to build an editor uniquely suited to your needs and workflow.

In many cases, using a fully-fledged IDE makes perfect sense. The advanced features may far outweigh any benefits you get from using Vim.

But, this is something for you to figure out yourself.

Despite its barebones nature, Vim has a thriving plugin ecosystem.

Vim has plugins for almost everything you can do with other editors. You just have to figure out which you need.

Something that surprised me was how far I can go with just a handful of plugins. My Vim setup currently comprises of around five or six ‘essential’ add-ons. I don’t really feel like I’m missing out on anything.

Vim is not perfect. And it is definitely not for everybody.

But at the very least, learn enough of Vim in case you accidentally open it and can’t figure out how to quit…! ;)