What is a promise?

A JavaScript promise is an object that represents the completion or failure of an asynchronous task and its resulting value.¹

The end.

I’m kidding of course. So, what does that definition even mean?

First of all, many things in JavaScript are objects. You can create an object a few different ways. The most common way is with object literal syntax:

const myCar = {

color: 'blue',

type: 'sedan',

doors: '4',

};You could also create a class and instantiate it with the new keyword.

class Car {

constructor(color, type, doors) {

this.color = color;

this.type = type;

this.doors = doors

}

}

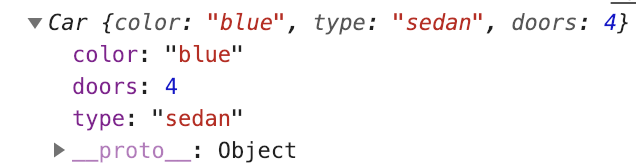

const myCar = new Car('blue', 'sedan', '4');console.log(myCar);

A promise is simply an object that we create like the later example. We instantiate it with the new keyword. Instead of the three parameters we passed in to make our car (color, type, and doors), we pass in a function that takes two arguments: resolve and reject.

Ultimately, promises tell us something about the completion of the asynchronous function we returned it from–if it worked or didn’t. We say the function was successful by saying the promise resolved, and unsuccessful by saying the promise rejected.

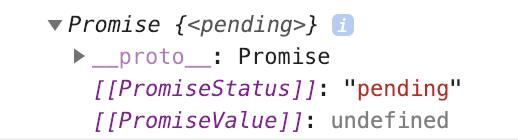

const myPromise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {});console.log(myPromise);

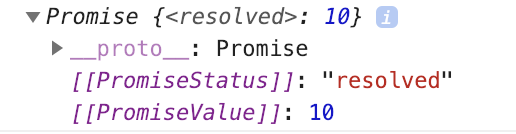

const myPromise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

resolve(10);

});

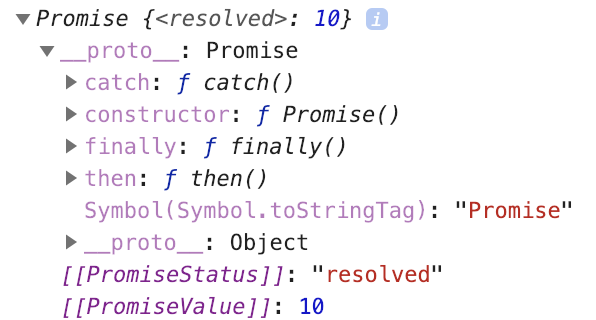

See, not too scary–just an object we created. And, if we expand it a bit:

In addition, we can pass anything we’d like to into resolve and reject. For example, we could pass an object instead of a string:

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

if(somethingSuccesfulHappened) {

const successObject = {

msg: 'Success',

data,//...some data we got back

}

resolve(successObject);

} else {

const errorObject = {

msg: 'An error occured',

error, //...some error we got back

}

reject(errorObject);

}

});Or, as we saw earlier, we don’t have to pass anything:

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

if(somethingSuccesfulHappend) {

resolve()

} else {

reject();

}

});What about the “asynchronous” part of the definition?

JavaScript is single threaded. This means it can only run one thing at a time. If you can imagine a road, you can think of JavaScript as a single lane highway. Certain code (asynchronous code) can slide over to the shoulder to allow other code to pass it. When that asynchronous code is done, it returns to the roadway.

As a side note, we can return a promise from any function. It doesn’t have to be asynchronous. That being said, promises are normally returned in cases where the function they return from is asynchronous. For example, an API that has methods for saving data to a server would be a great candidate to return a promise!

The takeaway:

Promises give us a way to wait for our asynchronous code to complete, capture some values from it, and pass those values on to other parts of our program.

I have an article here that dives deeper into these concepts: Thrown For a Loop: Understanding Loops and Timeouts in JavaScript.

How do we use a promise?

Using a promise is also called consuming a promise. In our example above, our function returns a promise object. This allows us to use method chaining with our function.

Here is an example of method chaining I bet you’ve seen:

const a = 'Some awesome string';

const b = a.toUpperCase().replace('ST', '').toLowerCase();

console.log(b); // some awesome ringNow, recall our (pretend) promise:

const somethingWasSuccesful = true;

function someAsynFunction() {

return new Promise((resolve, reject){

if (somethingWasSuccesful) {

resolve();

} else {

reject()

}

});

}And, consuming our promise by using method chaining:

someAsyncFunction

.then(runAFunctionIfItResolved(withTheResolvedValue))

.catch(orARunAfunctionIfItRejected(withTheRejectedValue));A (more) real example.

Imagine you have a function that gets users from a database. I’ve written an example function on Codepen that simulates an API you might use. It provides two options for accessing the results. One, you can provide a callback function where you can access the user or any error. Or two, the function returns a promise as a way to access the user or error.

Traditionally, we would access the results of asynchronous code through the use of callbacks.

rr someDatabaseThing(maybeAnID, function(err, result)) {

//...Once we get back the thing from the database...

if(err) {

doSomethingWithTheError(error)

} else {

doSomethingWithResults(results);

}

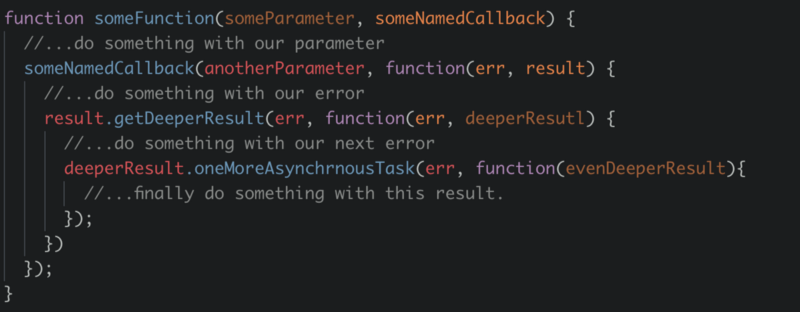

}The use of callbacks is ok until they become overly nested. In other words, you have to run more asynchronous code with each new result. This pattern of callbacks within callbacks can lead to something known as “callback hell.”

Promises offer us a more elegant and readable way to see the flow of our program.

doSomething()

.then(doSomethingElse) // and if you wouldn't mind

.catch(anyErrorsPlease);Writing our own promise: Goldilocks, the Three Bears, and a Supercomputer

Imagine you found a bowl of soup. You’d like to know the temperature of that soup before you eat it. You're out of thermometers, but luckily, you have access to a supercomputer that tells you the temperature of the bowl of soup. Unfortunately, this supercomputer can take up to 10 seconds to get the results.

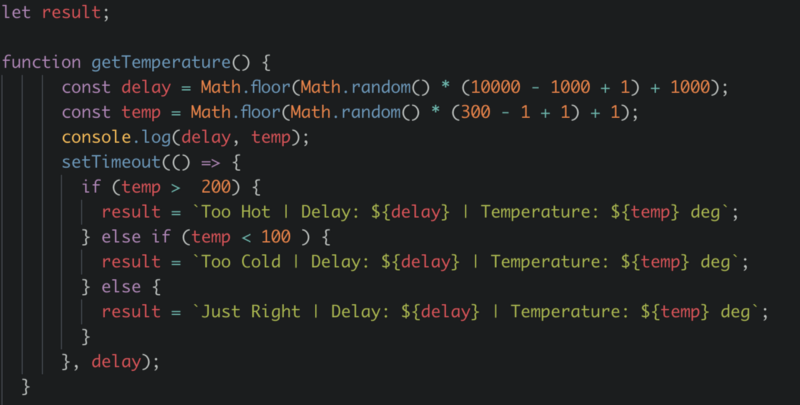

Here are a couple of things to notice.

- We initiate a global variable called

result. - We simulate the duration of the network delay with

Math.random()andsetTimeout(). - We simulate a temperature with

Math.random(). - We keep the delay and temperature values confined within a range by adding some extra “math”. The range for

tempis 1 to 300; the range fordelayis 1000ms to 10000ms (1s to 10 seconds). - We log the delay and temperature so we have an idea of how long this function will take and the results we expect to see when it’s done.

Run the function and log the results.

getTemperature();

console.log(results); // undefinedThe temperature is undefined. What happened?

The function will take a certain amount of time to run. The variable is not set until the delay is over. So while we run the function, setTimeout is asynchronous. The part of the code in setTimeout moves out of the main thread into a waiting area.

I have an article here that dives deeper into this process: Thrown For a Loop: Understanding Loops and Timeouts in JavaScript.

Since the part of our function that sets the variable result moves into a holding area until it is done, our parser is free to move onto the next line. In our case, it’s our console.log(). At this point, result is still undefined since our setTimeout is not over.

So what else could we try? We could run getTemperature() and then wait 11 seconds (since our max delay is ten seconds) and then console.log the results.

getTemperature();

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(result);

}, 11000);

// Too Hot | Delay: 3323 | Temperature: 209 degThis works, but the problem with this technique is, although in our example we know the maximum network delay, in a real-life example it might occasionally take longer than ten seconds. And, even if we could guarantee a maximum delay of ten seconds, if the result is ready sooner, we are wasting time.

Promises to the Rescue

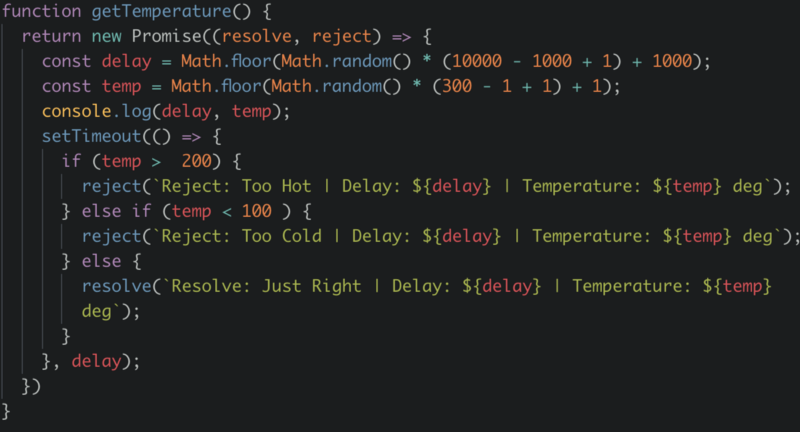

We are going to refactor our getTemperature() function to return a promise. And instead of setting the result, we will reject the promise unless the result is “Just Right,” in which case we will resolve the promise. In either case, we will pass in some values to both resolve and reject.

We can now use the results of our promise we are returning (also know as consuming the promise).

getTemperature()

.then(result => console.log(result))

.catch(error => console.log(error));

// Reject: Too Cold | Delay: 7880 | Temperature: 43 deg.then will get called when our promise resolves and will return whatever information we pass into resolve.

.catch will get called when our promise rejects and will return whatever information we pass into reject.

Most likely, you’ll consume promises more than you will create them. In either case, they help make our code more elegant, readable, and efficient.

Summary

- Promises are objects that contain information about the completion of some asynchronous code and any resulting values we want to pass in.

- To return a promise we use

return new Promise((resolve, reject)=> {}) - To consume a promise we use

.thento get the information from a promise that has resolved, and.catchto get the information from a promise that has rejected. - You’ll probably use (consume) promises more than you’ll write.

References

1.) https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Promise