by Mike Groseclose

In Defense of Hyper Modular JavaScript

Last week npmgate was a big topic for the JavaScript community. For those of you who haven’t been following what happened, here’s the TL;DR:

A company, named Kik, asked Azer Koçulu to give them the kik project name on npm. Azer said no (because he was already using it). Kik asked again, this time threatening to get lawyers involved for Trademark infringement. Azer forcefully said no and Kik escalated to npm. npm sided with Kik and moved ownership of the module away from Azer. In response Azer wrote I’ve Just Liberated My Modules and removed all of his packages from npm. One of the packages he removed was left-pad.

The removal of left-pad from npm essentially broke the install process for any project using it as a dependency. The impact of this was large as it was being used by a large number of very popular projects (Babel, Atom, and React to name a few).

The Internet caught on fire ?.

This all caused a number of questions to be raised, most of which can be categorized by the following:

- Was this a trademark infringement? A legal issue.

- Should npm have sided with Kik? A business issue.

- Should you be able to un-publish a module that is a dependency of another module? A technical concern.

- Should npm modules be mutable? A technical concern.

- Should the community use modules like left-pad as dependencies to begin with? A much larger discussion.

npm, and their legal team, will be the ones that ultimately need to figure out the business and legal issues (#1 & #2 above). It will be up to them to determine if this was truly was a trademark infringement and what the policy on requests like this will be going forward.

For #3 above (the ability to un-publish a module that is a dependency of another published module) npm has made the following statement:

npm needs safeguards to keep anyone from causing so much disruption. If these had been in place yesterday, this post-mortem wouldn’t be necessary.

- @izs from kik, left-pad, and npm

Although npm-shrinkwrap can help with some of the mutability issues (#4), the only real mitigation I have seen is to bundle your dependancies with your published package. Rich Harris explains this in his article How to not break the internet with this one weird trick.

So that leads us to #6, the reason this article exists:

Should the community use modules like left-pad as dependencies to begin with?

In order to understand why this is even a debate, we should first understand left-pad. Given a string (str), length (len), and character (ch), left-pad will pad the left side of str with ch until the string length equals len.

Here is the entirety of the code powering left-pad:

The idea that 17 lines of code (221 characters) was behind the implosion of the internet created a lot of complaints about the use of hyper-modular packages within the JavaScript community.

So with that, (finally) I begin.

npmgate had nothing to do with the size of the left-pad module

The size of left-pad is a red herring. How many lines of code it contains is completely irrelevant to the discussion of how its removal from the npm ecosystem broke other packages. It could have been the removal of any package from the ecosystem which caused this.

Azer removed 272 modules during his exodus from npm. It’s definitely safe to say that left-pad was written by a developer who has established himself in the community.

Those who argue that having a dependency like left-pad adds risk to their project are essentially arguing against having any external npm dependancies in their project.

Yes, we can all write modules like left-pad from scratch

But why would we want to?

The whole reason utility libraries like jQuery and lodash were created is to make the developer experience better.

Sure the code behind left-pad is not very complex and it could probably be rewritten by any of us in a few minutes. Some may even enjoy the detour. That said, context switching from writing code solving the problem at hand to writing a method that manipulates strings seems like a poor use of time and energy. Remember, just because we can do something doesn’t mean we should.

Everyday we should be enabling ourselves to focus on problems bigger and better than the day before.

Community

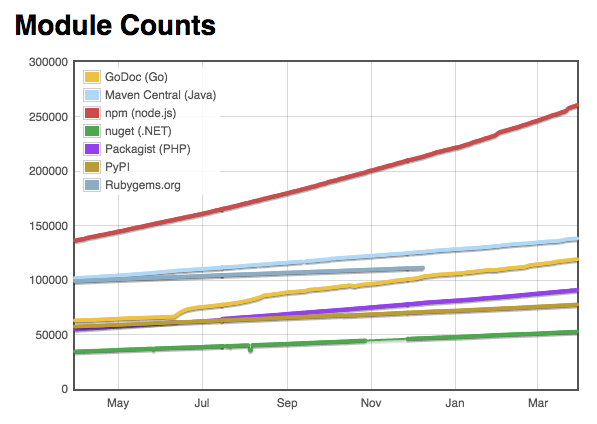

There is reason npm is outperforming all other package managers when it comes to growth. The barrier to entry to participate by publishing a package to npm is extremely small.

Enabling more developers to participate in the process, regardless of the contribution size, can only cause the community to grow stronger.

Free-market JavaScript

Standards will probably never be able to keep up with the momentum and speed at which the JavaScript community is moving. This is OK. In this new world of free-market JavaScript, may the best module win. Good modules should grow as they get more downloads and community involvement, whereas modules not used or supported will slowly disappear into the virtual abyss. In fact, there are cases, such as bluebird, where the community library will out-perform the standard library (see Why are native ES6 promises slower and more memory-intensive than bluebird?)

So with all these modules how do you know which modules are safe to use? The truth is, as with any open source software, you never know for sure. But here’s the litmus test I use when including anything from npm in my project:

- Is the package well documented?

- Does it have tests?

- Are people using it?

- Does the community have opinions about it (usually this only applies to larger modules)?

It’s not about size, it’s about functionality

The beauty of our ecosystem is that modular development encapsulates responsibility and forces a separation of concerns. The size of the module should be irrelevant to the discussion, whereas the functionality is key.

The strength of any good hyper-modular package is that it will have a well defined interface, clearly documented, and well tested. Don’t we want all of our code to be composed from modules like that?

Modules are about composability

Think of node modules as lego blocks. You don’t necessarily care about the details of how it’s made. All you need to know is how to use the lego blocks to build your lego castle. — Sindre Sorhus from AMA #10

In the end, this is all about composition. So, let’s continue building modules, let’s use those modules to build other modules, and those modules to build systems. Let’s compose those systems together to start building things that have never been done before.

Final note: I should be clear that I’m not saying that everything should be a tiny module. If anything, I’d like to see more large opinionated libraries in the community (another brain-dump for another day). In the meantime though, we should remember that some of the things being complained about right now are the same things that have made the JavaScript community so great.

Thanks.