More and more front-end developers are adopting unidirectional architectures. So what’s the future for the classic Model-View-Controller (MVC) approach?

In order to understand how we got to this point, let’s first review the evolution of front-end architecture.

Over the past four years, I’ve worked on a great deal of web projects and spent a good amount of time architecting front ends and integrating framework into them.

Before 2010, JavaScript — that programming language jQuery was written in — was used mostly for adding DOM manipulation to traditional websites. Developers didn’t seem to care much about the architecture itself. Things like the revealing module pattern were good enough to structure our codebases around.

Our current discussion of front-end vs back-end architecture only came about in late 2010. This is when developers started taking the concept of a single page application seriously. This is also when frameworks like Backbone and Knockout started to become popular.

Since many of the principles these frameworks were built around were quite new at the time, their designers had to look elsewhere for inspiration. They borrowed practices that were already well established for server-side architecture. And at that moment, all the popular server-side frameworks involved some sort of implementation of the classic MVC model (also known as MV* because of its variations).

When React.js was first introduced as a rendering library, many developers mocked it because they perceived its way of dealing with HTML in JavaScript as counter-intuitive. But they overlooked the most important contribution that React brought on the table — Component Based Architecture.

React did not invent components, but it did take this idea one step further.

This major breakthrough in architecture was overlooked even by Facebook, when they advertised React as the “V in the MVC.”

On a side note, I still have nightmares after reviewing a codebase which had both Angular 1.x and React working together.

2015 brought us a major shift in mindset — from the familiar MVC pattern to the Unidirectional Architectures and Data Flows derived from Flux and Functional Reactive Programming, supported by tools like Redux or RxJS.

So where did it all go wrong for MVC?

MVC is still probably the best way to deal with the server side. Frameworks like Rails and Django are a pleasure to work with.

The problems stem from the fact that the principles and separations that MVC introduced on the server aren’t the same as on the client.

Controller-View Coupling

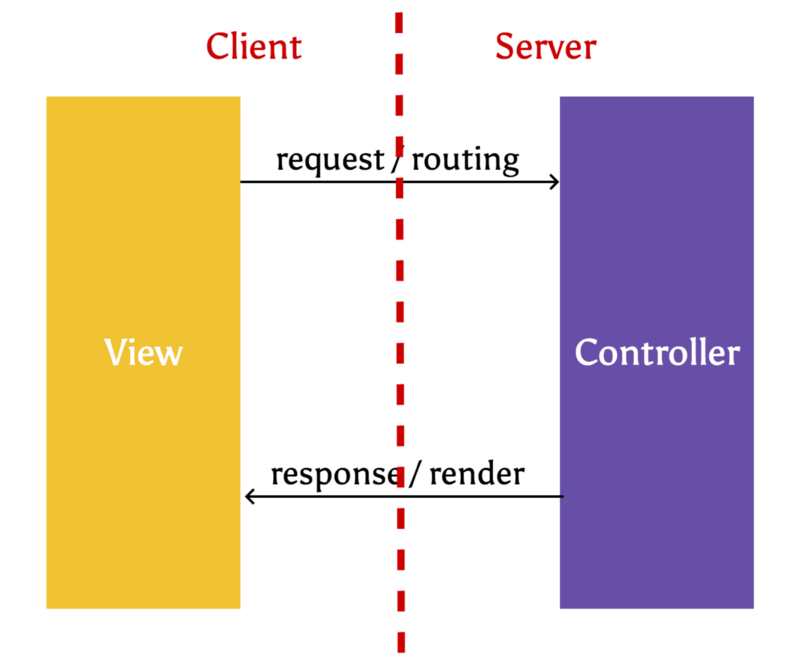

Below is a diagram of how the View and the Controller are interacting on the server. There are only two touch points between them, both crossing the boundary between the client and the server.

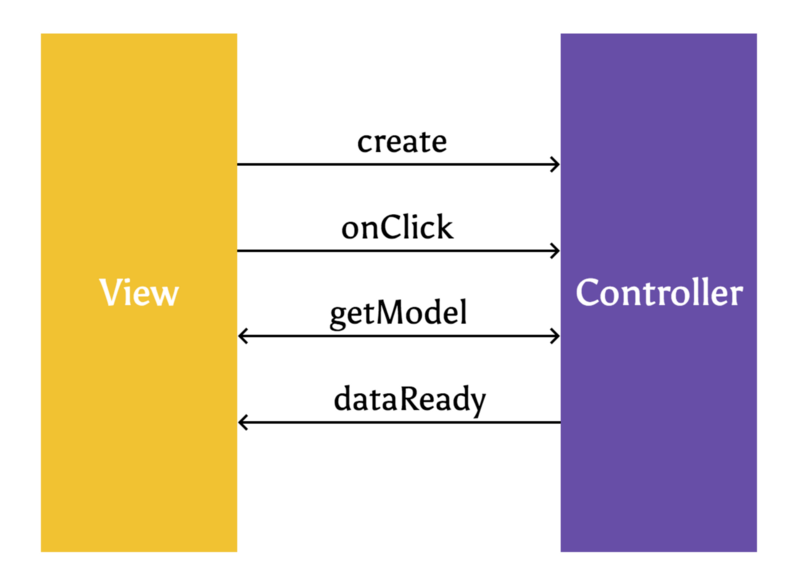

When you move to MVC on the client, there’s a problem. Controllers resemble what we call “code-behind.” The Controller is highly dependent on the View. In most framework implementations, it’s even created by the View (as is the case with, for example, ng-controller in Angular).

Additionally, when you think of the Single Responsibility Principle, this is clearly breaking the rules. The client controller code is dealing with both event handling and business logic, at a certain level.

Fat Models

Think a bit about the kind of data you store in a Model on the client side.

On one hand, you have data like users and products, which represent your Application State. On the other hand, you need to store the UI State — things like showTab or selectedValue.

Similar to the Controller, the Model is breaking the Single Responsibility Principle, because you don’t have a separate way of managing UI State and Application State.

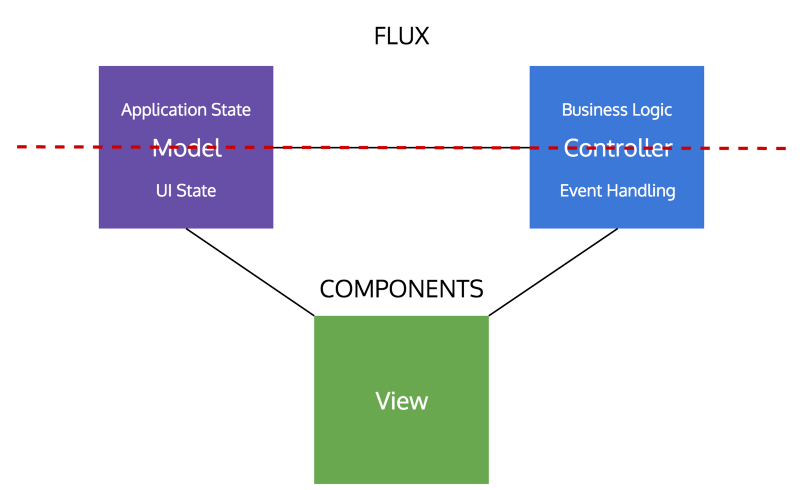

So where do components fit into this model?

Components are: Views + Event Handling+ UI State.

The diagram below shows how you actually split the original MVC model to obtain the components. What’s left above the line is exactly what Flux is trying to solve: managing Application State and Business Logic.

With the popularity of React and component-based architecture, we saw the rise of unidirectional architectures for managing application state.

One of the reasons these two go so well together so well is that they cover the classic MVC approach entirely. They also provide a much better separation of concerns when it comes to building front-end architectures.

But this is no longer a React story. If you look at Angular 2, you’ll see the exact same pattern being applied, even though you have different options for managing application state like ngrx/store.

There wasn’t really anything MVC could have done better on the client. It was doomed to fail from the beginning. We just needed time to see this. Through this five-year process, front-end architecture evolved into what it is today. And when you think about it, five years isn’t such a long time for best practices to emerge.

MVC was necessary in the beginning because our front end applications were getting bigger and more complex, and we didn’t know how to structure them. I think it served its purpose, while also providing a good lesson about taking a good practice from one context (the server) and applying it to another (the client).

So what does the future hold?

I don’t think that we will come back to the classic MVC architecture anytime soon for our front end apps.

As more and more developers start to see the advantages of components and unidirectional architectures, the focus will be on building better tools and libraries that go down that path.

Will this kind of architecture be the best solution five years from now? There’s a good chance of that happening, but then again, nothing is certain.

Five years ago, no one could have predicted how we would end up writing apps today. So I don’t think that it’s safe to place the bets for the future now.

That’s about it! I hope you enjoyed reading this. I welcome your feedback below.

If you liked the article, click on the green heart below and I will know my efforts are not in vain.