by Shalvah

Parsing math expressions with JavaScript

A while ago, I wrote about tokenizing a math expression, with Javascript as the language of choice. The tokenizer I built in that article was the first component of my quest to render and solve math expressions using Javascript, or any other language. In this article, I’ll walk through how to build the next component: the parser.

What is the job of the parser? Quite simple. It parses the expression. (Duh.) Okay, actually, Wikipedia has a good answer:

A parser is a software component that takes input data (frequently text) and builds a data structure — often some kind of parse tree, abstract syntax tree or other hierarchical structure — giving a structural representation of the input, checking for correct syntax in the process. The parsing may be preceded or followed by other steps, or these may be combined into a single step. The parser is often preceded by a separate lexical analyser, which creates tokens from the sequence of input characters

So, in essence, this is what we’re trying to achieve:

math expression => [parser] => some data structure (we'll get to this in a bit)

Let’s skip ahead a bit: “… The parser is often preceded by a separate lexical analyzer, which creates tokens from the sequence of input characters”. This is talking about the tokenizer we built earlier. So, our parser won’t be receiving the raw math expression, but rather an array of tokens. So now, we have:

math expression => [tokenizer] => list of tokens => [parser] => some data structureFor the tokenizer, we had to come up with the algorithm manually. For the parser, we’ll be implementing an already existing algorithm, the Shunting-yard algorithm. Remember the “some data structure” above? With this algorithm, our parser can give us a data structure called an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) or an alternative representation of the expression, known as Reverse Polish Notation (RPN).

Reverse Polish Notation

I’ll start with RPN. Again from Wikipedia, RPN is “a mathematical notation in which every operator follows all of its operands”. Instead of having, say, 3+4, RPN would be 3 4 +. Weird, I know. But the rule is that the operator has to come after all its operands.

Keep that rule in mind as we take a look at some more complex examples. Also remember that an operand for one operation can be the result of an earlier operation).

Algebraic: 3 - 4 RPN: 3 4 -Algebraic: 3 - 4 + 5 RPN: 3 4 - 5 +Algebraic: 2^3 RPN: 2 3 ^Algebraic: 5 + ((1 + 2) × 4) − 3 RPN: 5 1 2 + 4 * + 3 -Algebraic: sin(45) RPN: 45 sinAlgebraic: tan(x^2 + 2*x + 6) RPN: x 2 ^ 2 x * + 6 + tanBecause the operator has to come after its operands, RPN is also known as postfix notation, and our “regular” algebraic notation is called infix.

How do you evaluate an expression in RPN? There’s a simple algorithm I use:

Read all the tokens from left to right till you get to an Operator or Function. Knowing that the Operator/Function takes n arguments (for instance, for +, n = 2; for cos(), n = 1), evaluate the last n preceding arguments with the Operator/Function, and replace all of them (Operator/Function + operands) with the result. Continue as before, until there are no more Operators/Functions left to read. The only (Literal or Variable) token left is your answer.

(This is a simplified algorithm, which assumes the expression is valid. A couple indicators that the expression isn’t valid are if you have more than one token left at the end, or if the last token left is an Operator/Function.)

So, for something like 5 1 2 + 4 * + 3 −:

read 5read 1read 2read +. + is an operator which takes 2 args, so calculate 1+2 and replace with the result (3). The expression is now 5 3 4 * + 3 -read 4read *. * is an operator which takes two args, so calculate 3*4 and replace with the result, 12. The expression is reduced to 5 12 + 3 -read +. + is an operator which takes two args, so calculate 5+12, replace by the result, 17. Now, we have 17 3 -read 3read -. - is an operator which takes two args, so calculate 17-3. The result is 14.Hope you made an A in my little crash course on RPN. You did? OK, let’s move on.

Abstract Syntax Trees

Wikipedia’s definition here might not be too helpful for many of us: “a tree representation of the abstract syntactic structure of source code written in a programming language.” For this use case, we can think of an AST as a data structure that represents the mathematical structure of the expression. This is better seen than said, so let’s draw a rough diagram. I’ll start with an AST for the simple expression 3+4:

[+] / \[3] [4]Each [] represents a node in the tree. So you can see at a glance, that the two tokens are brought together by a the + operator.

A more complex expression, 5 + ((1 + 2) * 4) − 3:

[-] / \ [+] \___[3] / \ [5]__/ [*] / \ [+] [4] / \ [1] [2]Ah, a lovely little syntax tree. It links up all tokens and operators perfectly. You can see that evaluating this expression is much easier — just follow the tree.

So,why is an AST useful? It helps you represent the logic and structure of the expression correctly, making it easier for the expression to be evaluated. For instance, to evaluate the above expression, on our backend we could do something like this:

result = binaryoperation(+, 1, 2)result = binaryoperation(*, result, 4)result = binaryoperation(+, 5, result)result = binaryoperation(-, result, 3)return resultIn other words, for each operator (or function) node that the evaluator/compiler/interpreter encounters, it checks to see how many branches there are, and then evaluates the results of all those branches with the operator.

Okay, the crash course is over, now back to our parser. Our parser will convert the (tokenized) expression to RPN, and later to an AST. So let’s begin implementing it.

The Shunting-yard algorithm

Here’s the RPN version of the full algorithm (from our friend Wikipedia), and modified to fit with our tokenizer:

While there are tokens to be read:

1. Read a token. Let’s call it t2. If t is a Literal or Variable, push it to the output queue.3. If t is a Function,push it onto the stack.4. If t is a Function Argument Separator (a comma), pop operators off the stack onto the output queue until the token at the top of the stack is a Left Parenthesis.5. If t is an Operator:a. while there is an Operator tokenoat the top of the operator stack and eithertis left-associative and has precedence is less than or equal to that ofo, ortis right associative, and has precedence less than that ofo, popooff the operator stack, onto the output queue;

b. at the end of iteration push t onto the operator stack.6. If the token is a Left Parenthesis, push it onto the stack.

7. If the token is a Right Parenthesis, pop operators off the stack onto the output queue until the token at the top of the stack is a left parenthesis. Then pop the left parenthesis from the stack, but not onto the output queue.

8. If the token at the top of the stack is a Function, pop it onto the output queue.

When there are no more tokens to read, pop any Operator tokens on the stack onto the output queue.

Exit.

(Side note: in case you read the earlier article, I’ve updated the list of recognized tokens to include the Function Argument Separator, aka comma).

The algorithm above assumes the expression is valid. I made it this way so it’s easily understandable in the context of an article. You can view the full algorithm on Wikipedia.

You’ll observe a couple of things:

- We need two data structures: a stack to hold the functions and operators, and a queue for the output. If you aren’t familiar with these two data structures, here’s a primer for you: if you want to retrieve a value from a stack, you start with the last one you put in, whereas for a queue, you start with the first you put in.

// we'll use arrays to represent both of themvar outQueue=[];var opStack=[];- We need to know the associativity of the operators. Associativity simply means in what order an expression containing several operations of the same kind are grouped in the absence of parentheses. For instance, 2 + 3 + 4 is canonically evaluated from left to right (2+ 3 =5, then 5 + 4 =9), so + has a left associativity. Compare that to 2 ^ 3 ^ 4, which is evaluated as 2 ^81, not 8 ^4. Thus ^ has a right associativity. We’ll package the associativities of the operators well encounter in a Javascriptobject:

var assoc = { "^" : "right", "*" : "left", "/" : "left", "+" : "left", "-" : "left" };- We also need to know the precedence of the operators. The precedence is a sort of ranking assigned to operators, so we can know in what order they should be evaluated if they appear in the same expression. Operators with higher precedence get evaluated first. For instance, * has a higher precedence than +, so 2 + 3 * 4 gets evaluated as 2 + 12, and not 5 * 4, unless parentheses are used. + and – have the same precedence, so 3 + 5 – 2 can be evaluated as either 8–2 or 3+3. Again, we’ll package the operator precedences in an object:

var prec = { "^" : 4, "*" : 3, "/" : 3, "+" : 2, "-" : 2 };Now, lets update our Token class so that we can easily access the precedence and associativity via methods:

Token.prototype.precedence = function() { return prec[this.value]; }; Token.prototype.associativity = function() { return assoc[this.value]; };- We need a method that allows us to peek at the stack (to check the element at the top without removing it), and one that allows us to pop from the stack (retrieve and remove the item at the top). Fortunately, Javascript arrays already have a

pop()method, so all we need to do is implement apeek()method. (Remember, for stacks, the element at the top is the one we added last.)

Array.prototype.peek = function() { return this.slice(-1)[0]; //retrieve the last element of the array };So here’s what we have:

function tokenize(expr) { ... // just paste the tokenizer code here}function parse(inp){ var outQueue=[]; var opStack=[];Array.prototype.peek = function() { return this.slice(-1)[0]; };var assoc = { "^" : "right", "*" : "left", "/" : "left", "+" : "left", "-" : "left" };var prec = { "^" : 4, "*" : 3, "/" : 3, "+" : 2, "-" : 2 };Token.prototype.precedence = function() { return prec[this.value]; }; Token.prototype.associativity = function() { return assoc[this.value]; }; //tokenize var tokens=tokenize(inp); tokens.forEach(function(v) { ... //apply the algorithm here }); return outQueue.concat(opStack.reverse()); // list of tokens in RPN}I won’t delve into the algorithm’s implementation so I don’t bore you. It’s a pretty straightforward task, practically a word-for-word translation of the algorithm to code, so at the end of the day, here’s what we have:

The toString function simply formats our RPN list of tokens in a readable format.

And we can test out our infix-to-postfix parser:

var rpn = parse("3 + 4 * 2 / ( 1 - 5 ) ^ 2 ^ 3");console.log(toString(rpn));Output:

3 4 2 * 1 5 - 2 3 ^ ^ / +RPN!!

Time to plant a tree

Now, let’s modify our parser so it returns an AST.

To generate an AST instead of RPN, we’ll need to make a few modifications:

- We’ll create an object to represent a node in our AST. Each node has a value and two branches (which may be

null):

function ASTNode(token, leftChildNode, rightChildNode) { this.token = token.value; this.leftChildNode = leftChildNode; this.rightChildNode = rightChildNode;}- The second thing we’ll be doing is changing our output data structure to a stack. While the actual code for this is just to change the line

var outQueue = []tovar outStack = [](because it remains an array), the key change is in our understanding and treatment of this array.

Now, how is our infix-to-AST algorithm going to run? Basically, the same algorithm, with a few modifications:

- Instead of pushing a Literal or Variable token onto our

outQueue, we push a new node whose value is the token, and whose branches arenullonto ouroutStack - Instead of popping an Operator/Function token from the

opStack, we replace the top two nodes on theoutStackwith a single node whose value is the token, and that has those two as its branches. Let’s create a function that does that:

Array.prototype.addNode = function (operatorToken) { rightChildNode = this.pop(); leftChildNode = this.pop(); this.push(new ASTNode(operatorToken, leftChildNode, rightChildNode)); }3. Our parser should now return a single node, the node at the top of our AST. Its two branches will contain the two child nodes, whose branches will contain their children,and so on, in a recursive manner. For instance, for an expression like 3 + 4 * 2 / ( 1–5 ) ^ 2 ^ 3, we expect the structure of our output node to be like this (in a horizontal form):

+ => 3 => null => null => / => * => 4 => null => null => 2 => null => null => ^ => - => 1 => null => null => 5 => null => null => ^ => 2 => null => null => 3 => null => nullIn the diagram above, the => represent the branches of the node (the top node is the left branch, the bottom one is the right branch). Each node has two branches, and the nodes at the end of the tree have theirs pointing to null

So, if we put all this together, here is the code we come up with:

And if we demo it:

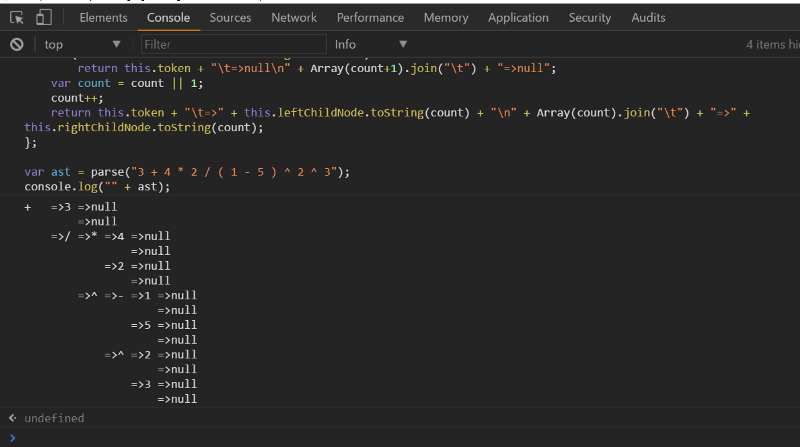

//a little hack I put together so it prints out in a readable formASTNode.prototype.toString = function(count) { if (!this.leftChildNode && !this.rightChildNode) return this.token + "\t=>null\n" + Array(count+1).join("\t") + "=>null"; var count = count || 1; count++; return this.token + "\t=>" + this.leftChildNode.toString(count) + "\n" + Array(count).join("\t") + "=>" + this.rightChildNode.toString(count);};var ast = parse("3 + 4 * 2 / ( 1 - 5 ) ^ 2 ^ 3");console.log("" + ast);And the result:

Slowly, but surely, we’re getting closer to understanding what makes compilers and interpreters tick! Admittedly, the working of modern-day programming languages and their toolkits is a lot more complex than what we’ve looked at thus far, but I hope this proves to be an easy-to-understand introduction to them. As a number of people have pointed out, tools exist to automatically generate tokenizers and parsers, but its often nice to know how something actually works.

The concepts we covered in this article and the previous are very interesting topics in the field of computer science and language theory. I still have a lot to learn about them, and I encourage you to go ahead and research them if they interest you. And drop me a line to let me know about your progress. Peace!