by Sanchit Gera

RESTful Services Part I : HTTP in a Nutshell

The web has, from it’s inception, been structured around the idea of resources. In it’s early days, the web was merely a platform for sharing simple text/HTML based files, documents, images etc. In this sense, the web can be thought of as a collection of resources and is often referred to as being resource-oriented.

The web has since evolved into a much more complex network of interconnected applications, brimming with rich content. Applications themselves have grown in complexity, packing increasing amounts of functionality within themselves.

Services provide a means for exposing this functionality to clients. Generally, large applications may want to provide programmatic access to their platform to other developers and may do so by making use of services.

Alternatively, services may be used to decompose an application into different logical units, interacting amongst themselves to produce some end result. In this case, a service acts as a consumer of other services.

With services forming a critical component to web applications, developers naturally try and ensure that they are designed in a way that is scalable, performant and work with as little overhead as possible — both technical and otherwise.

Enter REST! REST, short for REpresentational State Transfer, is an architectural style that aims to leverage all the same constructs that have allowed to the Web to grow over the last couple of decades. It uses these as guiding principles for designing web services.

Since all communication on the Web happens over HTTP, REST is intricately tied to it and uses a lot of the same ideas. As such, an understanding of REST requires an understanding the underlying concepts of HTTP. This is the subject of the remainder of this post. :)

HTTP in a Nutshell

Most web applications are built around a client-server model. A client could be something as simple as a web browser displaying plain old HTML, a mobile application fetching and creating data or even other web services.

Similarly, servers could be implemented in a variety of ways, using different technology stacks, languages, and serving different types of data.

In order to accommodate this diversity, clients and servers must agree upon a set of conventions — a protocol — that dictates all communication between them. This protocol allows a web server to receive the information — requests — sent by an arbitrary client, process them, and respond appropriately.

Modern day web applications use the Hypertext Transfer Protocol, commonly abbreviated to HTTP, in order to exchange information.

Essentially, this provides a structured format for exchange of information over the web. As we shall see, HTTP lays down a broad set of guidelines in order to describe the type of data being exchanged — along with it’s format, validity, and other attributes.

In the past, applications have typically relied on HTTP solely as a transmission mechanism. Clients and servers exchange data using HTTP. Other conventions must then be developed in order to make sense of that data. One example of such a paradigm is SOAP, one of the most common opponents of REST.

The wonderful thing about HTTP, however, is that it already has the constructs needed in order to specify the action and the resource being acted upon (client request), as well as the outcome of those actions (server response), which prevents for additional overhead to transfer information. Let’s take a look at some of them!

1. URLs

The URL are a one of the most important and useful concepts of the Web. It is also probably the concept most users are already familiar with, even if only in passing. URL is short for Uniform Resource Locator and is used to identify the address of a resource on the Web.

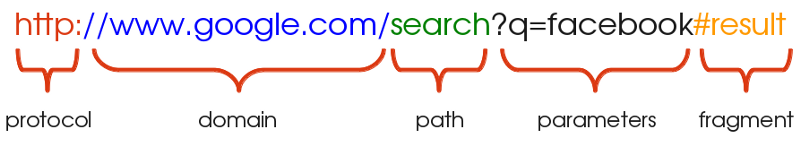

A URL typically consists of the following components :

Protocol: This is the protocol that the request is served over. This is most often just HTTP (or its secure version, HTTPS). Other protocols such as SMTP and FTP exist and may be used instead, but we will limit ourselves to HTTP in this discussion.

Domain: This is the host name of the server the resource is being requested from. The domain may be equivalently replaced by an IP address, which is usually done under the hood by a DNS.

Path: This is the location of the resource on the server. This may be correspond to the location of the resource within the file system (i.e. /search/files/myFile.txt) although this practice is rarely used nowadays. It is more common for web services to nest paths based on relationship between resources (i.e. myBlog/blog/comments) where blog and comments represent two distinct resources. This is explored further in the second part of this series.

Parameters: This is additional data, passed in the form of key-value pairs, that may be used by the server to identify the resource, or filter a list of resources.

Fragment: A fragment refers to a location within the resource being returned and is typically applied to documents. This may be thought of as a bookmark within the document returned and instructs the browser to locate the content at the bookmarked point and display it. For example, for HTML documents the browser directly scrolls to the element identified by the anchor. Fragments are also referred to as anchors.

2. HTTP Methods

HTTP defines a handful of methods, also called “verbs”, that a client may use in order to describe the type of request being made. This is best understood in the context of resources discussed previously.

Each request can be modeled as doing a specific action on a resource. For example, a client may request to create, delete, update or simply read from a resource. In HTTP this corresponds to making POST, DELETE, PUT or GET requests respectively. POST and PUT requests accept payloads corresponding to the data being created or updated. We will explore the these methods in detail when we get to talking about REST in the next part.

Two additional methods, which are used much less frequently, are the OPTIONS and HEAD methods.

Simply, the purpose of an OPTIONS request is to give the client information about what other methods may be used to interact with the resource in question.

The HEAD request, on the other hand, is a little more useful. A HEAD request mimics a GET request, except that it omits the body of the response. Essentially, the client receives a response identical to what it would have received for a GET request, with the same meta data, but without the response body. This is useful as it provides a quick way to check the response headers and existence of a resource.

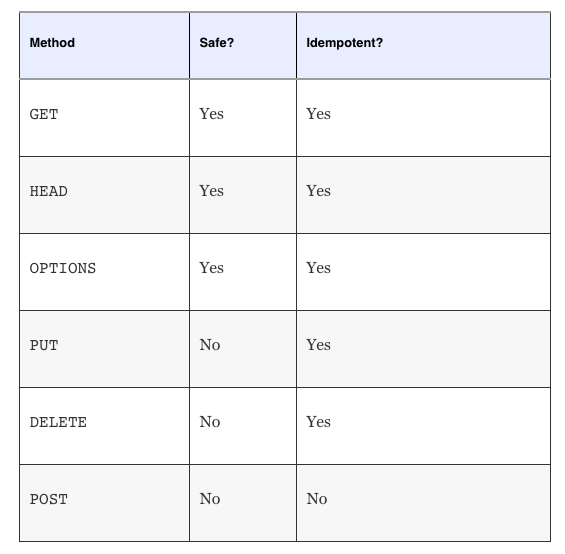

One important distinction laid down by HTTP is whether a method is safe or unsafe. A method is said to be safe if it doesn’t modify a resource. In other words, the request may be thought of as “read-only.” For example, making a GET (or HEAD) request for a resource from a server should not modify it in any way. All other methods are by default unsafe.

Lastly, there is the concept of idempotence. An HTTP method is said to be idempotent if repeated invocations of a request lead to the same outcome. As long as the parameters of the request remain unchanged, the request could be made any number of times and the resource would still be left in the same state as if the request were made only once. This fits well with the notion of resource-oriented thinking.

GET, OPTIONS and HEAD are all naturally idempotent methods, as they are read-only operations. Additionally the PUT and DELETE methods are also characterized as idempotent. This is because updating any resource with the same set of parameters over and over again leads to the same end result.

It may be slightly unintuitive for some to see why DELETE is also idempotent. Consider what happens to the system when multiple DELETE requests are made simultaneously. The first DELETE requests results in, well, the deletion of the resource. Making more DELETE requests at this point does not modify the state that the system is in. The system continues to remain in the same state that it were in after the first DELETE executed.

To summarize…

3. Status Codes

Status codes are a useful HTTP construct that provide information to the consumer about the outcome of a request and how to interpret it. For example, if I were to make a request to retrieve a file from a web server, I would expect to see a response with the status code describing whether or not my request was completed successfully. If not, the status code would give me a further clue as to why my request failed.

HTTP defines several status codes, each pertaining to a specific scenario. Some of the common series of codes you might encounter are listed here:

2xx: Status codes falling in the 2xx series imply that the request completed successfully and without errors. Code 200 is the typical example.

3xx: A code in the 3xx series implies redirection. This means that the server redirected to another location on receiving the request.

4xx: A 4xx error, i.e. 400, 403, 404 etc. are used when there is an error in the request made. This could be caused by a variety of reasons, such as unauthorized access to a resource, trying to work with a resource that doesn’t actually exist, invalid parameters and so on.

5xx: Lastly, a 5xx response is used when there is an error on the server side. This means that the server is aware of the error and is incapable of processing the request. Typically, the response is accompanied by a brief description of what the cause of the error might be.

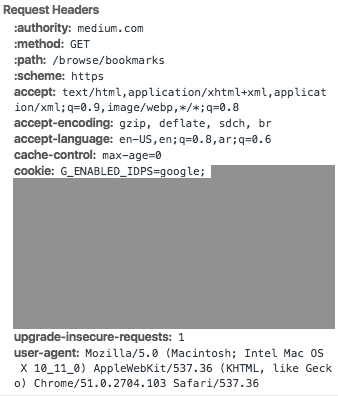

4. HTTP Headers

Headers are an essential part of HTTP communication. They serve to provide additional information for handling requests and responses. Note that the headers do not relate to the identification of the resource that is being acted upon. They typically appear as key value pairs and provide a host of information such as the cache policy for the response, the acceptable response types enforced by the client, the preferred language of response, encoding, etc.

Credentials for authentication and authorization — such as access tokens — are also commonly passed using the Authorization header.

Similarly, the server may also make use of response headers to set cookies on the client and analogously retrieve them with the same mechanism.

A note on HTTPS: To avoid confusion, it is also important to understand what HTTPS is and how it differs from regular HTTP. Both HTTP and HTTPS use the same underlying mechanisms for transferring information, although HTTPS is (far) more secure. Data transferred over HTTPS is fully encrypted. This is an important consideration when the information in question is confidential, such as financial data or a user’s personal information.

In the next part of this post, I discuss the constraints put in place by REST on top of HTTP, and how it leverages the resource based nature of the Web to design simple and scalable web services. Find it here!

And finally, in the third and last part of this series, you will learn about the The Richardson Maturity Model, a way to quantifiably measure how RESTful a service is, or isn’t. Check it out! :-)

Other recommended reading: