Typing code can help you develop a learning mindset

Want to break some code? Change it real quick before you even understand what it does.

Now you’re practicing Cargo Cult programming — a style of software development where you ignore how a piece of code works and its relationship with the code around it.

The term cargo cult programmer may apply when a computer programmer that is inexperienced with the problem at hand copies some code from one place to another with little or no understanding of how it works or whether it is required in its new position.

— Cargo Cult Programming on Wikipedia

When a developer copies a piece of code that they don't understand and uses it in the hope of fixing some problem, they’re practicing Cargo Cult programming. This increases the risk of unintended side-effects.

When a developer reads a piece of code that they don't understand and still changes it in the hope of fixing some problem, they’re also practicing Cargo Cult programming.

The problem, in this case, is not that the developer is copying something. Anyone can copy a snippet of code, understand it, learn from it, use it, and still have a lower risk of unintended side-effects.

Cargo Cult programming, on the other hand, represents a fundamental misunderstanding of proven steps for learning from other people's code.

Here’s the most efficient way to learn in this context:

- Read a piece of code.

- Understand all features of the language that are being used there.

- Understand all the features of the libraries/frameworks that are being used there.

- Learn the basics of those libraries/frameworks.

- Understand what every line does and the purpose of those libraries/frameworks in the context of that piece of code.

For someone who starts working with a new language, this is going to be extremely hard. The amount of information a human needs to retain to efficiently understand even a small snippet of code is so huge that it might be forgotten right away. What we can do is leverage certain aspects of how the human brain is used to learning things — consciously or unconsciously — with some proven techniques.

One of those techniques is blocked practice. It’s basically where you learn by “performing a single skill over and over, with repetition being the key.”

This isn’t the best way to learn, though. It’s proven that, when you learn through interleaving different variations of the same skill, you’ll learn more efficiently.

In software engineering, we can leverage both blocked and interleaving learning practices when we type the code in different contexts, instead of just copying and pasting it.

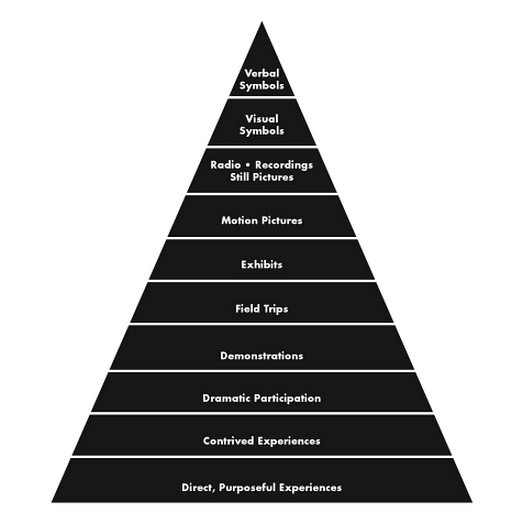

When copy-pasting snippets, we’re just reading (if we even bother doing that). And according to the relationship of the Cone of Experience, we might learn only a small portion of the information we consume because it’s too abstract.

Contrast this with learning better by actually typing out that piece of code. This is a more direct and purposeful experience. It forces your brain to understand all those different patterns and learn more efficiently.

Typing code instead of copy-pasting it provides a better learning ROI because we’re practicing instead of just reading.

Naming things is considered one of the most difficult aspects of programming. When we copy code without understanding it, we run the risk of breaking something by overwriting variable names, function names, or classes.

If we instead understand the code first, then type it up in our own words, we can rename things in a way that suits our app and ensures we don’t have any naming collisions, even if the final result is functionally the same as the piece of code we’re basing upon.

Besides that, if we copy the code from one place in our codebase to another, there’s a chance that we’ll copy tokens that are unnecessary or forget to change tokens that should have been changed.

Take the following HTML snippet, for example:

<label for="name"></label>

<div class="input-wrapper">

<input type="text" id="name">

</div>When duplicating that code to create a new input, we’re likely to forget to change the for attribute of the label element, which will break the intended behavior for the new input.

<label for="name"></label>

<div class="input-wrapper">

<input type="text" id="name">

</div>

<label for="name"></label>

<div class="input-wrapper">

<input type="password" id="password">

</div>This example is interesting because it’s the kind of functionality that is hard to test, even with visual regression. It heavily depends on static testing — like a code review — to make sure that the code was written for the intended purpose. (In this case, to propagate mouse events to the input for the same id of the label for attribute.)

The same thing happens with tests. When we copy an already passing test instead of creating a new one from the scratch, we run the risk of not changing necessary tokens that would otherwise cause that test to fail.

In this case, though, we can prevent this mistake by using Test Driven Development — a mindset based on creating a failing test first, then change the application code to make it pass. This mindset allows us to be confident that we’re less likely to miss something or create false-positives.

Instead of copying code without understanding it, learn from other people's code and practice on top of it. This will maximize your learning ROI.

After all, the most valuable resource of a developer is the brain — not the fingers.

Thanks for reading. If you have some feedback, reach out to me on Twitter, Facebook or Github.