by William W Wold

I wrote a programming language. Here’s how you can, too.

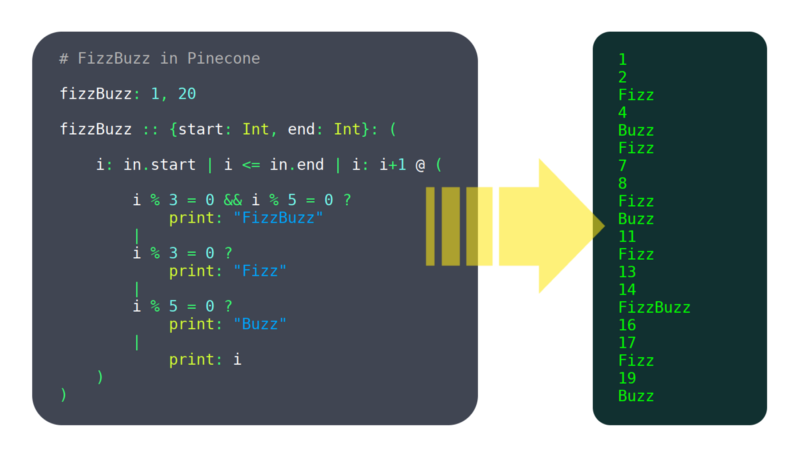

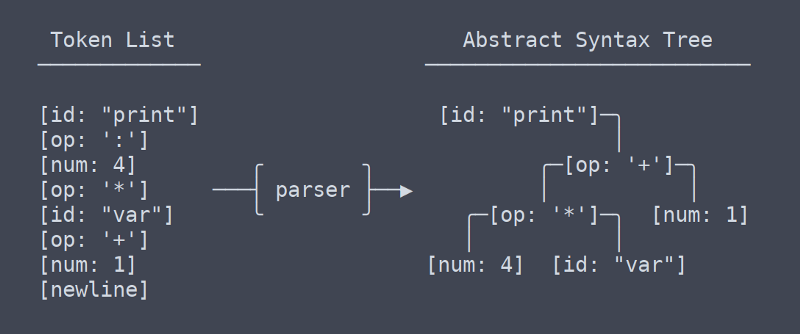

Over the past 6 months, I’ve been working on a programming language called Pinecone. I wouldn’t call it mature yet, but it already has enough features working to be usable, such as:

- variables

- functions

- user defined structures

If you’re interested in it, check out Pinecone’s landing page or its GitHub repo.

I’m not an expert. When I started this project, I had no clue what I was doing, and I still don’t. I’ve taken zero classes on language creation, read only a bit about it online, and did not follow much of the advice I have been given.

And yet, I still made a completely new language. And it works. So I must be doing something right.

In this post, I’ll dive under the hood and show you the pipeline Pinecone (and other programming languages) use to turn source code into magic.

I‘ll also touch on some of the tradeoffs I’ve had make, and why I made the decisions I did.

This is by no means a complete tutorial on writing a programming language, but it’s a good starting point if you’re curious about language development.

Getting Started

“I have absolutely no idea where I would even start” is something I hear a lot when I tell other developers I’m writing a language. In case that’s your reaction, I’ll now go through some initial decisions that are made and steps that are taken when starting any new language.

Compiled vs Interpreted

There are two major types of languages: compiled and interpreted:

- A compiler figures out everything a program will do, turns it into “machine code” (a format the computer can run really fast), then saves that to be executed later.

- An interpreter steps through the source code line by line, figuring out what it’s doing as it goes.

Technically any language could be compiled or interpreted, but one or the other usually makes more sense for a specific language. Generally, interpreting tends to be more flexible, while compiling tends to have higher performance. But this is only scratching the surface of a very complex topic.

I highly value performance, and I saw a lack of programming languages that are both high performance and simplicity-oriented, so I went with compiled for Pinecone.

This was an important decision to make early on, because a lot of language design decisions are affected by it (for example, static typing is a big benefit to compiled languages, but not so much for interpreted ones).

Despite the fact that Pinecone was designed with compiling in mind, it does have a fully functional interpreter which was the only way to run it for a while. There are a number of reasons for this, which I will explain later on.

Choosing a Language

I know it’s a bit meta, but a programming language is itself a program, and thus you need to write it in a language. I chose C++ because of its performance and large feature set. Also, I actually do enjoy working in C++.

If you are writing an interpreted language, it makes a lot of sense to write it in a compiled one (like C, C++ or Swift) because the performance lost in the language of your interpreter and the interpreter that is interpreting your interpreter will compound.

If you plan to compile, a slower language (like Python or JavaScript) is more acceptable. Compile time may be bad, but in my opinion that isn’t nearly as big a deal as bad run time.

High Level Design

A programming language is generally structured as a pipeline. That is, it has several stages. Each stage has data formatted in a specific, well defined way. It also has functions to transform data from each stage to the next.

The first stage is a string containing the entire input source file. The final stage is something that can be run. This will all become clear as we go through the Pinecone pipeline step by step.

Lexing

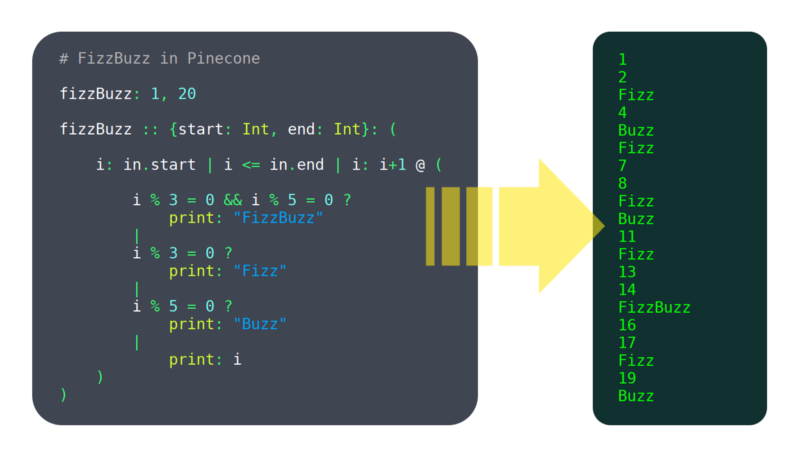

The first step in most programming languages is lexing, or tokenizing. ‘Lex’ is short for lexical analysis, a very fancy word for splitting a bunch of text into tokens. The word ‘tokenizer’ makes a lot more sense, but ‘lexer’ is so much fun to say that I use it anyway.

Tokens

A token is a small unit of a language. A token might be a variable or function name (AKA an identifier), an operator or a number.

Task of the Lexer

The lexer is supposed to take in a string containing an entire files worth of source code and spit out a list containing every token.

Future stages of the pipeline will not refer back to the original source code, so the lexer must produce all the information needed by them. The reason for this relatively strict pipeline format is that the lexer may do tasks such as removing comments or detecting if something is a number or identifier. You want to keep that logic locked inside the lexer, both so you don’t have to think about these rules when writing the rest of the language, and so you can change this type of syntax all in one place.

Flex

The day I started the language, the first thing I wrote was a simple lexer. Soon after, I started learning about tools that would supposedly make lexing simpler, and less buggy.

The predominant such tool is Flex, a program that generates lexers. You give it a file which has a special syntax to describe the language’s grammar. From that it generates a C program which lexes a string and produces the desired output.

My Decision

I opted to keep the lexer I wrote for the time being. In the end, I didn’t see significant benefits of using Flex, at least not enough to justify adding a dependency and complicating the build process.

My lexer is only a few hundred lines long, and rarely gives me any trouble. Rolling my own lexer also gives me more flexibility, such as the ability to add an operator to the language without editing multiple files.

Parsing

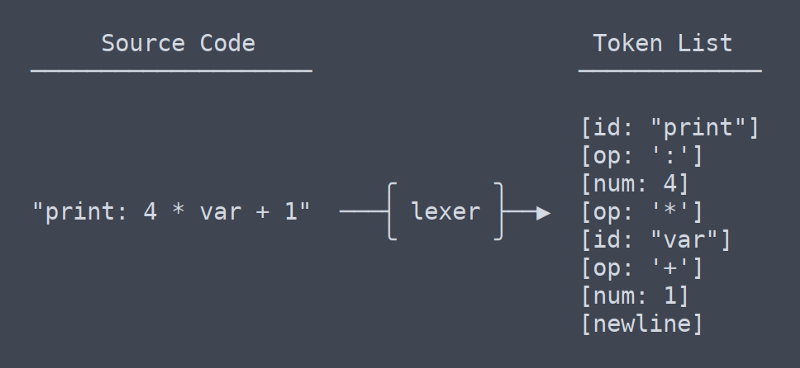

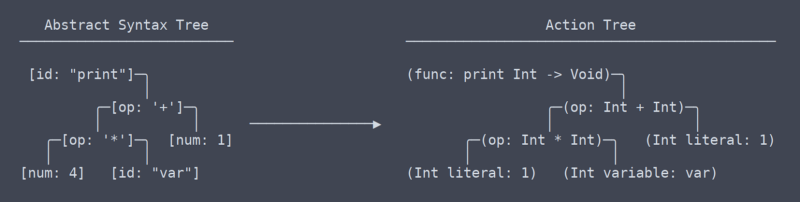

The second stage of the pipeline is the parser. The parser turns a list of tokens into a tree of nodes. A tree used for storing this type of data is known as an Abstract Syntax Tree, or AST. At least in Pinecone, the AST does not have any info about types or which identifiers are which. It is simply structured tokens.

Parser Duties

The parser adds structure to to the ordered list of tokens the lexer produces. To stop ambiguities, the parser must take into account parenthesis and the order of operations. Simply parsing operators isn’t terribly difficult, but as more language constructs get added, parsing can become very complex.

Bison

Again, there was a decision to make involving a third party library. The predominant parsing library is Bison. Bison works a lot like Flex. You write a file in a custom format that stores the grammar information, then Bison uses that to generate a C program that will do your parsing. I did not choose to use Bison.

Why Custom Is Better

With the lexer, the decision to use my own code was fairly obvious. A lexer is such a trivial program that not writing my own felt almost as silly as not writing my own ‘left-pad’.

With the parser, it’s a different matter. My Pinecone parser is currently 750 lines long, and I’ve written three of them because the first two were trash.

I originally made my decision for a number of reasons, and while it hasn’t gone completely smoothly, most of them hold true. The major ones are as follows:

- Minimize context switching in workflow: context switching between C++ and Pinecone is bad enough without throwing in Bison’s grammar grammar

- Keep build simple: every time the grammar changes Bison has to be run before the build. This can be automated but it becomes a pain when switching between build systems.

- I like building cool shit: I didn’t make Pinecone because I thought it would be easy, so why would I delegate a central role when I could do it myself? A custom parser may not be trivial, but it is completely doable.

In the beginning I wasn’t completely sure if I was going down a viable path, but I was given confidence by what Walter Bright (a developer on an early version of C++, and the creator of the D language) had to say on the topic:

“Somewhat more controversial, I wouldn’t bother wasting time with lexer or parser generators and other so-called “compiler compilers.” They’re a waste of time. Writing a lexer and parser is a tiny percentage of the job of writing a compiler. Using a generator will take up about as much time as writing one by hand, and it will marry you to the generator (which matters when porting the compiler to a new platform). And generators also have the unfortunate reputation of emitting lousy error messages.”

Action Tree

We have now left the the area of common, universal terms, or at least I don’t know what the terms are anymore. From my understanding, what I call the ‘action tree’ is most akin to LLVM’s IR (intermediate representation).

There is a subtle but very significant difference between the action tree and the abstract syntax tree. It took me quite a while to figure out that there even should be a difference between them (which contributed to the need for rewrites of the parser).

Action Tree vs AST

Put simply, the action tree is the AST with context. That context is info such as what type a function returns, or that two places in which a variable is used are in fact using the same variable. Because it needs to figure out and remember all this context, the code that generates the action tree needs lots of namespace lookup tables and other thingamabobs.

Running the Action Tree

Once we have the action tree, running the code is easy. Each action node has a function ‘execute’ which takes some input, does whatever the action should (including possibly calling sub action) and returns the action’s output. This is the interpreter in action.

Compiling Options

“But wait!” I hear you say, “isn’t Pinecone supposed to by compiled?” Yes, it is. But compiling is harder than interpreting. There are a few possible approaches.

Build My Own Compiler

This sounded like a good idea to me at first. I do love making things myself, and I’ve been itching for an excuse to get good at assembly.

Unfortunately, writing a portable compiler is not as easy as writing some machine code for each language element. Because of the number of architectures and operating systems, it is impractical for any individual to write a cross platform compiler backend.

Even the teams behind Swift, Rust and Clang don’t want to bother with it all on their own, so instead they all use…

LLVM

LLVM is a collection of compiler tools. It’s basically a library that will turn your language into a compiled executable binary. It seemed like the perfect choice, so I jumped right in. Sadly I didn’t check how deep the water was and I immediately drowned.

LLVM, while not assembly language hard, is gigantic complex library hard. It’s not impossible to use, and they have good tutorials, but I realized I would have to get some practice before I was ready to fully implement a Pinecone compiler with it.

Transpiling

I wanted some sort of compiled Pinecone and I wanted it fast, so I turned to one method I knew I could make work: transpiling.

I wrote a Pinecone to C++ transpiler, and added the ability to automatically compile the output source with GCC. This currently works for almost all Pinecone programs (though there are a few edge cases that break it). It is not a particularly portable or scalable solution, but it works for the time being.

Future

Assuming I continue to develop Pinecone, It will get LLVM compiling support sooner or later. I suspect no mater how much I work on it, the transpiler will never be completely stable and the benefits of LLVM are numerous. It’s just a matter of when I have time to make some sample projects in LLVM and get the hang of it.

Until then, the interpreter is great for trivial programs and C++ transpiling works for most things that need more performance.

Conclusion

I hope I’ve made programming languages a little less mysterious for you. If you do want to make one yourself, I highly recommend it. There are a ton of implementation details to figure out but the outline here should be enough to get you going.

Here is my high level advice for getting started (remember, I don’t really know what I’m doing, so take it with a grain of salt):

- If in doubt, go interpreted. Interpreted languages are generally easier design, build and learn. I’m not discouraging you from writing a compiled one if you know that’s what you want to do, but if you’re on the fence, I would go interpreted.

- When it comes to lexers and parsers, do whatever you want. There are valid arguments for and against writing your own. In the end, if you think out your design and implement everything in a sensible way, it doesn’t really matter.

- Learn from the pipeline I ended up with. A lot of trial and error went into designing the pipeline I have now. I have attempted eliminating ASTs, ASTs that turn into actions trees in place, and other terrible ideas. This pipeline works, so don’t change it unless you have a really good idea.

- If you don’t have the time or motivation to implement a complex general purpose language, try implementing an esoteric language such as Brainfuck. These interpreters can be as short as a few hundred lines.

I have very few regrets when it comes to Pinecone development. I made a number of bad choices along the way, but I have rewritten most of the code affected by such mistakes.

Right now, Pinecone is in a good enough state that it functions well and can be easily improved. Writing Pinecone has been a hugely educational and enjoyable experience for me, and it’s just getting started.