Often, JavaScript just works. And because it is written in human-readable syntax, certain things seem intuitive. But it’s easy to ignore what’s happening on a deeper level. Eventually, though, this lack of understanding results in an inability to solve a problem.

Intuition is the ability to understand something immediately, without the need for conscious reasoning. — Google

I spend a fair amount of time trying to solve two-dimensional problems, and a slightly larger portion of it trying to solve three-dimensional ones.

While I enjoy practicing coding in my off time, by day I am an air traffic controller. The problems we face as air traffic controllers aren’t different than any other job. There are routine problems with routine solutions and unique problems with unique solutions. It’s through a deeper understanding that we can solve the unique ones.

From the outside looking in at air traffic control, it may seem everything is a unique problem–that there is an inherent requisite skill to do the job. However, while certain aptitudes can make learning any skill easier, it is ultimately experience that drives problem-solving to a subconscious level. The result is intuition.

Intuition follows observation. Observe a unique problem enough times, and it and its solution become routine. It’s noticing the consistencies across each situation where we begin to develop a sense of what should happen next.

Intuition does not, however, require a deep understanding. We can often point to the correct solution, without being able to articulate how or why it works. Sometimes, however, we choose solutions which seem intuitive but are in fact governed by an unfamiliar set of rules.

What does this code output?

for(var i = 1; i < 6; i++) {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(i);

},1000);

}

console.log('The loop is done!');Take some time to think about what this code will output. We will begin to build the foundation to answer this, and we will return to this later.

JavaScript is a language dialect.

I grew up in the Northeastern United States. Although I speak English, my speech undeniably contains regional variety. This variety is called dialect. My particular dialect is an implementation (or version) of the English language standard.

It may seem standards would give birth to dialects, but it is the dialect which initially drives the need for standards. JavaScript is similar. JavaScript is the dialect, not the standard. The standard is ECMAScript, created by ECMA–the European Computer Manufacturers Association. ECMAScript is an attempt to standardize JavaScript.

There is more than one implementation of ECMAScript, but JavaScript happens to be the most popular, and therefore, the name JavaScript and ECMAScript are often used interchangeably.

JavaScript runs in an engine.

JavaScript is only a text file. Like a driver without a car, it can’t go very far. Something has to run or interpret your file. This is done by a JavaScript engine.

A few examples of JavaScript engines include V8, the engine used by Google Chrome; SpiderMonkey, the engine used by Mozilla Firefox; and JavaScriptCore, the engine used by Apple Safari. ECMAScript, the language standard, ensures consistency across the different JavaScript engines.

JavaScript engines run in an environment.

While JavaScript can run in different places (for example, Node.js, a popular server-side technology, runs JavaScript and uses the same V8 engine that Google Chrome uses), the most common place to find a JavaScript engine is a web browser.

Within the browser, the JavaScript engine is just one part of a larger environment that helps bring our code to life. There are three main parts to this environment, and together they make up what is termed the runtime environment.

The call stack

The first part is the location of the currently running code. This is named the call stack. There’s only one call stack in JavaScript, and this will become important as we continue to build our foundation.

Here is a simplified example of the call stack:

function doSomething() {

//some other code

doSomethingElse();

//some other code

}

function doSomethingElse() {

//some other code

}

doSomething();The initial call stack is empty, as there is no running code. When our JavaScript engine finally reaches the first function invocation, doSomething(), it gets added to the stack:

--Call Stack--

doSomething;Inside of doSomething() we run some other code and then reach doSomethingElse():

--Call Stack--

doSomething

doSomethingElseWhen doSomethingElse() is done running, it is removed from the call stack:

--Call Stack--

doSomethingFinally, doSomething() finishes the remaining code, and is also removed from the call stack:

--Call Stack--

EmptyWeb APIs

The second part of our browser environment fills somewhat of a void. Surprisingly, things such as interacting with the DOM, making server requests, and most browser-based tasks are not part of the ECMAScript language standard.

Fortunately, browsers offer us added features that our JavaScript engine can plug in to. These features extend the functionality of JavaScript within the browser. They allow us to do things such as listen for events or make server requests — things that JavaScript can’t do by itself. And they are called web APIs.

Many web APIs allow us to listen or wait for something to occur. When that event occurs, we then run some other code.

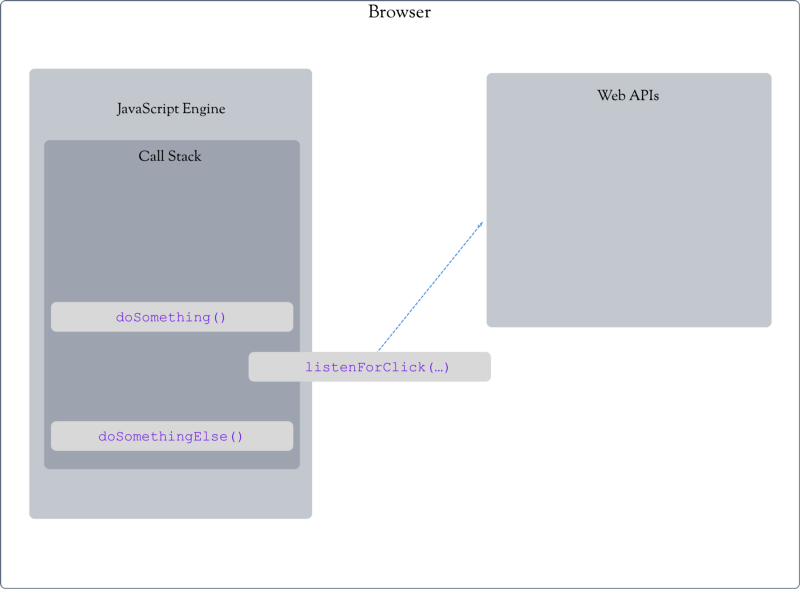

Here is our call stack example expanded to include a (pretend) web API.

function doSomething() {

//some other code

listenForClick();

doSomethingElse();

//some other code

}

function doSomethingElse() {

//some other code

}

listenForClick() {

console.log('the button was clicked!')

}

doSomething();When the browser encounters doSomething() it gets placed in the call stack:

--Call Stack--

doSomethingThen, it runs some other code and then encounters listenForClick(...):

--Call Stack--

doSomething

listenForClicklistenForClick() gets plugged into a web API, and in this case, it is removed from our call stack.

The JavaScript engine now moves on to doSomethingElse():

--Call Stack--

doSomething

doSomethingElsedoSomethingElse() and doSomething() finish, and the call stack is empty. But what happened to listenForClick()?

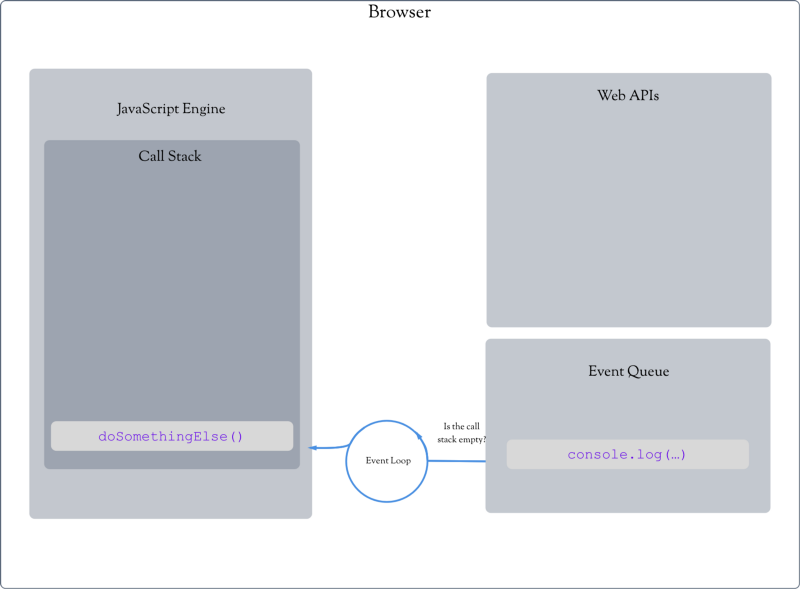

Event Queue

This is where we introduce the final part of our browser environment. Often, our web API code is a function that takes a callback. A callback is just some code we want to run after another function runs. For example, listening for a click event and then console.log something. In order to make sure our console.log doesn’t interfere with any currently running code, it first passes to something called an event queue.

The event queue acts as a waiting area until our call stack is empty. Once the call stack is empty, the event queue can pass our code into the call stack to be run. Let’s continue to build upon our previous example:

function doSomething() {

//some other code

listenForClick();

doSomethingElse();

//some other code

}

function doSomethingElse() {

//some other code

}

listenForClick() {

console.log('the button was clicked!')

}

doSomething();So now, our code runs like this:

Our engine encounters doSomething():

--Call Stack--

doSomethingdoSomething() runs some code and then encounters listenForClick(...). In our example, this takes a callback, which is the code we want to run after the user clicks a button. The engine passes listenForClick(…) out of the call stack and continues until it encounters doSomethingElse():

--Call Stack--

doSomething

doSomethingElsedoSomethingElse() runs some code, and finishes. By this time, our user clicks the button. The web API hears the click and sends the console.log() statement to the event queue. We’ll pretend doSomething() is not done; therefore, the call stack is not empty, and the console.log() statement must wait in the event queue.

--Call Stack--

doSomethingAfter a few seconds, doSomething() finishes and is removed from the call stack:

--Call Stack--

EMPTYFinally, the console.log() statement can get passed into the call stack to be executed:

--Call Stack--

console.log('The user clicked the button!')Keep in mind, our code is running incredibly fast — taking single-digit milliseconds to finish. It isn’t realistic we could start our code, and our user could click a button before the code is done running. But in our simplified example, we pretend that this is true, to highlight certain concepts.

Together, all three parts (the call stack, the web APIs, and the event queue) form what is called the concurrency model, with the event loop managing the code that goes from the event queue into the call stack.

Take aways from the above examples:

JavaScript can only do one thing at a time.

There is a misconception that people can multi-task. This isn’t true. People can, however, switch between tasks, a process called task switching.

JavaScript is similar in the sense that it can’t multitask. Because JavaScript has only one call stack, the JavaScript engine can only do one task at a time. We say this makes JavaScript single threaded. Unlike people, however, JavaScript can’t task switch without the help of our web APIs.

JavaScript must finish a task before moving on.

Because JavaScript can’t switch back and forth between tasks, if you have any code that takes a while to run, it will block the next line of code from running. This is called blocking code, and it happens because JavaScript is synchronous. Synchronous simply means that JavaScript must finish a task before it can start another one.

An example of blocking code might be a server request which requires us to wait for data to be returned. Fortunately, the web APIs provided by the browser give us a way around this (with the use of callbacks).

By moving blocking code from the call stack into the event loop, our engine can move on to the next item in the call stack. Therefore, with code running in our call stack, and code that is simultaneously running in a web API, we have asynchronous behavior.

Not all web APIs, however, go into the event loop. For example, console.log is a web API, but since it has no callback and doesn’t need to wait for anything, it can be executed immediately.

Do keep in mind that single threaded is not the same as synchronous. Single threaded means “one thing at a time.” Synchronous means “finish before moving on.” Without the help of asynchronous APIs, core JavaScript is both single threaded and synchronous.

The scoop on scope

Before we return to our original question, we need to touch on scope. Scope is the term used to describe which parts of our code have access to which variables.

Intuitively, it may seem that a variable declared and initialized by a for loop would only be available within that for loop. In other words, if you tried to access it outside of the loop, you would get an error.

This isn’t the case. Declaring a variable with the var keyword creates a variable that is also available in its parent scope.

This example shows that a variable declared by var within a for loop is also available within the parent scope (in this case, the global scope).

for(var a = 1; a < 10; a++) {} // declared "inside" the loop

console.log(a); // prints "10" and is called "outside the loop"The answer revealed

At this point, we’ve discussed enough to build our answer.

Here is our example revisited:

for(var i = 1; i < 6; i++) {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(i);

},1000);

}

console.log('The loop is done!');Intuitively, you might believe this will print the numbers one through five, with one second between each number being printed:

// one second between each log

1

2

3

4

5

The loop is done!However, what we actually output is:

The loop is done!

// then about one second later and all at once

6

6

6

6

6What’s happening?

Recall our discussion about web APIs. Asynchronous web API’s, or those with callbacks, go through the event loop. setTimeout()happens to be an asynchronous web API.

Every time we loop, setTimeout() is passed outside of the call stack and enters the event loop. Because of this, the engine is able to move to the next piece of code. The next piece of code happens to be the remaining iterations of the loop, followed by console.log(‘The loop is done!’).

To show the setTimeout() statements are being passed from the call stack, and the loop is running, we can place a console.log() statement outside of the setTimeout() function and print the results. We can also place a built-in timer method to show just how quickly everything is happening. We use console.time() and console.timeEnd() to do this .

console.time('myTimer');

for(var i = 1; i < 6; i++) {

console.log('Loop Number' + i); // added this

setTimeout(()=>{

console.log(i);

},1000);

}

console.log('The loop is done!');

console.timeEnd('myTimer');Results:

Loop Number 1

Loop Number 2

Loop Number 3

Loop Number 4

Loop Number 5

The loop is done!

// then, about one second later and all at once:

6

6

6

6

6

myTimer: 1.91577ms // Wow, that is quick!First, we can see the loop is in fact running. In addition, the timer we added tells us that everything other than our setTimeout() functions took less than two milliseconds to run! That means each setTimeout() function has about 998 milliseconds remaining before the code it contains goes into the event queue and then finally into the call stack. Remember earlier when I said it would be difficult for a user to be faster than our code!

If you run this code multiple times, you will likely notice the timer output will change slightly. This is because your computer’s available resources are always changing and it might be slightly faster or slower each time.

So here is what’s happening:

- Our engine comes across our for loop. We declare and initialize a global variable named

iequal to one. - Each iteration of loop passes

setTimeout()to a web API and into the event loop. Therefore, ourfor loopfinishes very quickly, since there is no other code inside of it to run. In fact, the only thing our loop does is change the value ofito six. - At this point, the loop is over, our

setTimeout()functions are still counting down, and all that remains in the call stack isconsole.log(‘The loop is done!’). - Fast forward a bit, and the

setTimeout()functions have finished, and theconsole.log(i)statements go into the event queue. By this time, ourconsole.log(‘The loop is done!’)has been printed and the call stack is empty. - Since the call stack is empty, the five

console.log(i)statements get passed from the event queue into the call stack. - Remember,

iis now equal to six, and that’s why we see five sixes printed to the screen.

Let’s create the output we thought we would get

Up to this point, we’ve discussed the actual output of a few simple lines of code that turned out to be not-so-simple. We’ve talked about what’s happening on a deeper level and what the result is. But, what if we want to create the output we thought we would get? In other words, how can we reverse engineer the following results:

1 // after one second, then

2 // one second later (2 seconds total)

3 // one second later (3 seconds total)

4 // one second later (4 seconds total)

5 // one second later (5 seconds total)

'The loop is done!' // one second later (6 seconds total)Does the duration on our timeout change anything?

Setting the timeout’s duration to zero seems like a possible solution. Let’s give it a try.

for(var i = 1; i < 6; i++) {

setTimeout(()=>{

console.log(i);

},0);

}

console.log('The loop is done!');Results:

// Everything appears (essentially) at once

The loop is done!

6

6

6

6

6It still didn’t work. What happened?

Remember, just because the duration of setTimeout() is zero, it is still asynchronous and handled by a web API. Regardless of the duration, it will be passed to the event queue and then the call stack. So even with a timeout of zero, the process remains the same, and the output is relatively unchanged.

Notice I said relatively. One thing you may have noticed that was different, was everything printed almost at once. This is because the duration of setTimeout() expires instantly, and its code gets from the web API, into the event queue, and finally into the call stack almost immediately. In our previous example, our code had to wait 1000 milliseconds before it went into the event queue and then the call stack.

So, if changing the duration to zero didn’t work, now what?

Revisiting Scope

What will this code output?

function myFunction1() {

var a = 'Brandon';

console.log(a);

}

function myFunction2() {

var a = 'Matt';

console.log(a);

}

function myFunction3() {

var a = 'Bill';

console.log(a);

}

myFunction1()

myFunction2()

myFunction3()Notice how each function uses the same variable named a. It would seem each function might throw an error, or possibly overwrite the value of a.

Results:

Brandon

Bill

MattThere is no error, and a is unique each time.

It appears the variable a is unique to each function. It’s very similar to how an address works. Street names and numbers are invariably shared across the world. There is more than a single 123 Main St. It’s the city and state which provide scope to which address belongs where.

Functions work in the same way. Functions act as a protective bubble. Anything inside of that bubble can’t be accessed by anything outside. This is why the variable a is not actually the same variable. It’s three different variables located in three different places in memory. They just so happen to all share the same name.

Applying the principles of scope to our example:

We know we have access to the iterative value of i, just not when the setTimeout() statements finish. What if we take the value of i and package it with the setTimeout() statement in its own bubble (as a way to preserve i)?

for(var i = 1; i < 6; i++) {

function timer(){ // create a unique function (scope) each time

var k = i; // save i to the variable k which

setTimeout(()=>{

console.log(k);

},1000);

}

timer();

}Result:

The loop is done!

1

2

3

4

5It almost works. What did we do?

We are beginning to get into the topic of closures. A deep discussion on closures goes beyond the scope of this article. However, a brief introduction will help our understanding.

Remember, each function creates a unique scope. Because of this, variables with the same name can exist in separate functions and not interfere with each other. In our most recent example, each iteration created a new and unique scope (along with a new and unique variable k). When the for loop is done, these five unique values of k are still in memory and are accessed appropriately by our console.log(k) statements. That is closure in a nutshell.

In our original example where we declare i with var, each iteration overwrote the value of i (which in our case was a global variable).

ES6 makes this much cleaner.

In 2015, ECMAScript released a major update to its standards. The update contained many new features. One of those features was a new way to declare variables. Up to this point, we have used the var keyword to declare variables. ES6 introduced the let keyword.

for(let i = 1; i < 6; i++) {

setTimeout(()=>{

console.log(i);

},1000);

}

console.log('The loop is done!');Results:

The loop is done!

1

2

3

4

5Just by changing var to let, we are much closer to the result we want.

A brief introduction to “let” vs “var”

In our example, let does two things:

First, it makes i available only inside our for loop. If we try to log i outside of the loop, we get an error. This is because let is a block scope variable. If it is inside a block of code (such as a for loop) it can only be accessed there. var is function scoped.

An example to show let vs var behavior:

function variableDemo() {

var i = 'Hello World!';

for(let i = 1; i < 3; i++) {

console.log(i); // 1, 2, 3

}

console.log(i); // "Hello World!"

// the for-loop value of i is hidden outside of the loop with let

}

variableDemo();

console.log(i); //Error, can't access either value of iNotice how we don’t have access to either i outside of the function variableDemo(). This is because ‘Hello World’ is function scoped, and i is block scoped.

The second thing let does for us is create a unique value of i each time the loop iterates. When our loop is over, we have created six separate values of i that are stored in memory that our console.log(i) statements can access. With var, we only had one variable that we kept overwriting.

The loop is not done.

We’re almost there. We still are logging 'The loop is done!' first, and we aren’t logging everything one second apart. First, we will look at two ways to address the The loop is done! output.

Option 1: Using setTimeout() and the concurrency model to our advantage.

This is fairly straightforward. We want The loop is done! to pass through the same process as the console.log(i) statements. If we wrap The loop is done! in a setTimeout() whose duration is greater to or equal than the for loop timeouts, we ensure The loop is done! arrives behind and expires after the last for loop timeouts.

We’ll break up our code a bit to make it a bit clearer:

function loopDone() { // we will call this below

console.log('The loop is done!)'

}

for(let i = 1; i < 6; i++) {

setTimeout(()=>{

console.log(i);

},1000);

}

setTimeout(loopDone, 1001);Results:

1

2

3

4

5

The loop is done!Option 2: Check for the final console.log(i) completion

Another option is to check when the console.log(i) statements are done.

function loopDone() {

console.log('The loop is done!');

}

for(let i = 1; i < 6; i++) {

setTimeout(()=>{

console.log(i);

if(i === 5){ // check when the last statement has been logged

loopDone();

}

},1000);

}Results:

1

2

3

4

5

The loop is done!Notice that we placed our loop completion check within the setTimeout() function, not within the main body of the for loop.

Checking when the loop is done won’t help us, since we still must wait for the timeouts to complete. What we want to do is check when the console.log(i) statements are done. We know this will be after the value of i is 5 and after we’ve logged it. If we place our loop completion check after the console.log(i) statement, we can ensure we’ve logged the final i before we run loopDone().

Getting everything to happen one second apart.

Everything is happening essentially at the same time because the loop is so fast, and all the timeouts arrive at the web API within milliseconds of each other. Therefore, they expire around the same time and go to the event queue and call stack around the same time.

We can’t easily change when they arrive at the web API. But we can, with the unique value of each i, delay how long they stay there.

function loopDone() {

console.log('The loop is done!');

}

for(let i = 1; i < 6; i++) {

setTimeout(()=>{

console.log(i);

if(i === 5){

loopDone();

}

},i * 1000); // multiple i by 1000

}Since i is now unique (because we are using let), if we multiply i by 1000, each timeout will last one second longer than the previous timeout. The first timeout will arrive with a 1000 millisecond duration, the second with 2000 and so forth.

Although they arrive at the same time, it will now take each timeout one second longer than the previous to pass to the event queue. Since our call stack is empty by this point, it goes from the event queue immediately into the call stack to be executed. With each console.log(i) statement arriving one second apart in the event queue, we will almost have our desired output.

1 // after one second, then

2 // one second later (2 seconds total)

3 // one second later (3 seconds total)

4 // one second later (4 seconds total)

5 // one second later (5 seconds total)

'The loop is done!' // still occurs with the final logNotice that The loop is done! is still arriving with the last console.log(i) statement, not one second after it. This is because when i===5 loopDone() is run. This prints both the i and The loop is done! statements around the same time.

We can simply wrap loopDone() in a setTimeout() to address this.

function loopDone() {

console.log('The loop is done!');

}

for(let i = 1; i < 6; i++) {

setTimeout(()=>{

console.log(i);

if(i === 5){

setTimeout(loopDone, 1000); // update this

}

},i * 1000);

}Results:

1 // after one second, then

2 // one second later (2 seconds total)

3 // one second later (3 seconds total)

4 // one second later (4 seconds total)

5 // one second later (5 seconds total)

'The loop is done!' // one second later (6 seconds total)We finally have the results we wanted!

Most of this article stemmed from my own struggles and the subsequent aha! moments in an attempt to understand closures and the JavaScript event loop. I hope this can make sense of the basic processes at play and serve as a foundation for more advanced discussions of the topic.

Thanks!

woz