by Josh Bowen

Want to learn something? Research it and present your work.

When I’m learning about something, I eventually hit a plateau. It’s hard to fight past this feeling. I’ve found that researching and then presenting that research helps me get unstuck.

You don’t have to be a student or professor to do this. I encourage everyone to try it. Just as posting your code on GitHub adds to open source, presenting (and publishing) your research adds to the body of scientific knowledge.

Creating a project

I started this project in January 2017 to learn more about machine learning and cyber security. Both are topics I’ve read about but have never applied. Since I didn’t know the current state of research in either area, I decided to tackle a problem in cyber security.

After a bit of sifting I found a government report from 2009. It described current problems and areas that need more research. I was drawn to the section on Insider Threats, so I decided to apply machine learning to insider threats.

I thought to myself — How hard can it be?

I was excited about the project, but hadn’t yet read any papers in the area. I started thinking of ways to evaluate how the average person uses a computer versus an insider with malicious intent. Because my laptop runs Ubuntu and I’m often in the terminal, the idea of looking at commands came to mind.

I decided I would capture commands as they happen, make evaluations, and try to stop malicious and mistake commands in their tracks. I didn’t know what I was getting myself into. I wrote an abstract (available here) and got to work.

The Research

A month later, I had done some (minimal) preliminary research. I then submitted my abstract to the AZ/NV Academy of Science. Since they accepted it, I seemed to be on the right path.

I had been in no rush to get anything done. I had months to go before presenting! This was a bad mindset. By the time my poster was accepted I had only five weeks to prepare. I raced to gather a reasonable body of research to build upon.

To my surprise, I found quite a few papers that have taken a stab at this problem. In fact, someone tried the same approach I chose back in 1999 and their research was proven ineffective a few years later! How could I go on?

I continued to read from the stack of papers I built up. Then it dawned on me that nobody was actually applying this stuff to a real-life situation. There was my differentiator: a practical application.

The Data

Before I could start writing code, I needed data for my machine learning model. I had about 60,000 commands in my own .zsh_history file but that was not enough. It also didn’t contain many mistakes and there as no malicious behavior.

I decided to solicit businesses for their logs — maybe I could get enough. Then it occurred to me to check whether anyone had already collected any databases of commands.

It turns out, Purdue University collected a large dataset of UNIX commands over a few years. And the University of California, Irvine saved it. I was in business.

Both my history file and the UNIX data had unnecessary bits I needed to get rid of. So I wrote some Python to deal with it because I didn’t want to go through 100,000+ lines by hand. First up was my history file. Not too difficult.

# Examples of what I'm dealing with: 1474850643:0;ls: 1474851038:0;cd# Examine each line and write to outputfor line in file: before, sep, after = line.rpartition(";") output.write(after.rstrip())The difficult part was handling the Purdue data. It was full of things like EOF, SOF, representations of arguments, flags, and pipes that were all on separate lines.

I had to figure out how those went together so I wasn’t feeding my model gibberish. I came up with a messy jumble of nested if statements nearly 50 lines long.

I’ve never been more excited and disappointed about code I’ve written. It is difficult to be proud of such a mess. But I spent so many hours on it that I was relieved to have something that worked.

Both programs saved everything in a CSV format for easy upload to Amazon’s S3 service. From there it is imported to the machine learning model and evaluated.

The Software

Now that I’d handled the data, I could finally start writing the demo program. How hard could it be?

I had less than three weeks to go. It was easy enough to send and receive from Amazon’s machine learning API. Making evaluations based on those responses was not too difficult either. I even knew how I would handle malicious and mistake commands.

But I knew nothing about capturing what the user was typing before the command was executed. I read the Python docs and tried the examples. I scoured the internet, and even looked in the Linux e-books I got in a Humble Bundle. Nothing. I spent almost half my time going down a road to nowhere.

I finally gave up and posted on Stack Overflow seeking a guru to guide me in the right direction. I am thankful that Ian responded. Even though it wasn’t the answer I was looking for, it was the answer I needed:

Okay sounds like it would be really useful. So why have you decided not to just do something like while(input=raw_input(“user: “)): #ML code if itsAllGood: subprocess(input.split()) else: #shutItDown

Ian Harvey — Mar 21 at 4:30

I had just over a week left. I ran with it, and wrote a simple program that creates a fake prompt, reads input, and evaluates the command. You can find the full program here.

There was a big problem with this program. Even though I passed KeyboardInterrupt and SystemExit, Ctrl + C would allow anyone to bypass the program.

The other big issue was that many commands didn't work, like cd. It was laughably bad, but I set it up on a Raspberry Pi and invited some hackers to give it a try. Needless to say my program didn't last long.

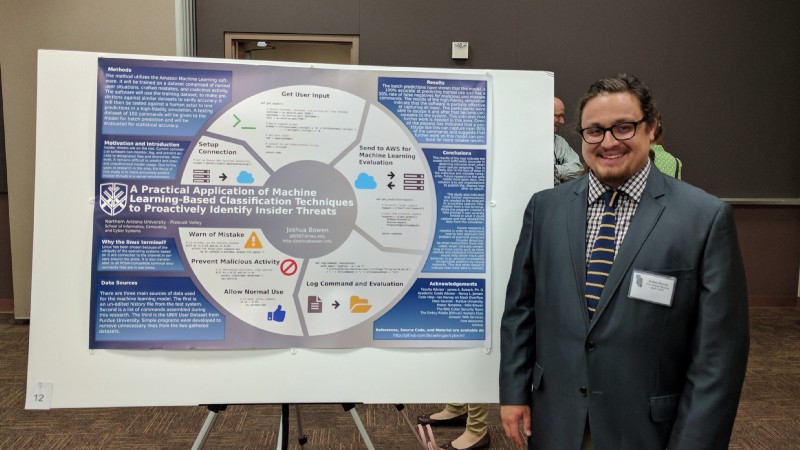

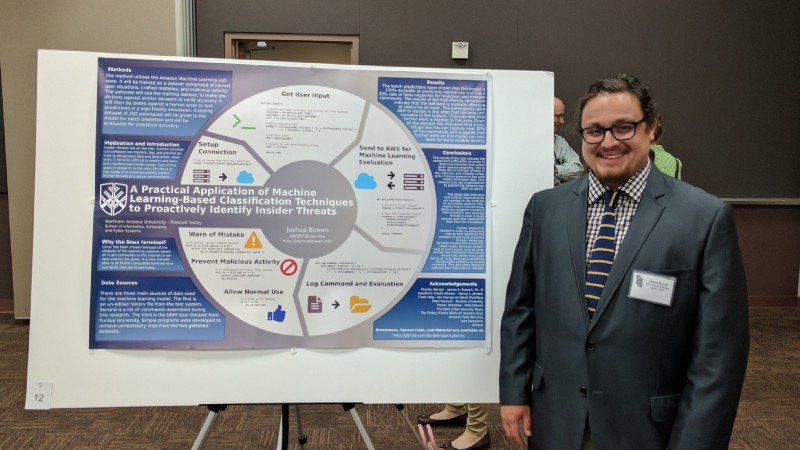

The Poster

Did you know that the standard for designing academic posters is Power Point? I couldn’t believe it. Unfortunately there isn’t an alternative. Whoever builds Prezi for academic posters can have my money.

I ended up finding a beautiful SVG poster used for math research and converted it for my project. At first this was brilliant. I’m used to Inkscape, and wouldn’t have to worry about scale when I sized things up. The downside was that I had to delete all the mathematical symbols one by one.

Writing content for the poster was a challenge. I had difficulty getting my thoughts into words. It came out all wrong in my first couple drafts. I also didn’t realize how big I needed to make the font so it would be readable from a few feet away.

I needed something to set my poster apart. I thought about explaining insider threats or machine learning as concepts. In the end, I settled for attempting to explain the demo software so that anyone could understand. I wrote simple titles and used some Font Awesome icons to demonstrate the point.

Afterward, I realized there was still too much empty space. I added snippets of code for each section. It was only later that I realized this might help demystify code for my audience. They were mostly science — but not computer science — students and professors.

The Presentation

I was nervous about presenting my poster. I was worried that people would ask complex questions about machine learning. Or that they would judge me because it turned out that this project was “unsuccessful.”

I was wrong. Everyone I spoke with was interested and understood the project’s failures. Some even thought the design was nice. Nobody asked the complex technical questions I was worried about.

But I should’ve practiced first — I didn’t have a very concise, five minute presentation ready to go.

Final Thoughts

So, what did I learn from this project? We need more open data. The machine learning model was skewed because the majority of data I had fell into the normal category. Businesses should release cleaned logs after a breach. Then that data could help develop models that could effectively stop similar attacks.

This approach won’t really work until I find a way to read commands as the user enters them while allowing the terminal to function normally. I will need to take into account custom commands, aliases, and what constitutes someone’s “normal” behavior. Adding variables such as typing speed and access data could help as well.

I plan to continue working on this project because I believe it can be viable.

I encourage all of you to pursue your ideas, take on projects to learn new things, and never give up.

If you enjoyed this post, give me some claps so more people see it. I write about machine learning, cyber security, IoT, and learning to code. Find me on twitter or my website.