by Alex Nadalin

Web Security: an introduction to HTTP

This is part 2 of a series on web security: part 1 was “Understanding The Browser”

HTTP is a thing of beauty: a protocol that has survived longer than 20 years without changing much.

As we’ve seen in the previous article, browsers interact with web applications through the HTTP protocol, and this is the main reason we’re drilling down on the subject. If users would enter their credit card details on a website and an attacker would be able to intercept the data before it reaches the server, we would definitely be in trouble.

Understanding how HTTP works, how we can secure the communication between clients and servers, and what security-related features the protocol offers is the first step towards improving our security posture.

When discussing HTTP, though, we should always discern between the semantics and technical implementation, as they’re two very different aspects of how HTTP works.

The key difference between the two can be explained with a very simple analogy: 20 years ago people cared about their relatives as much as they do now, even though the way they interact has substantially changed. Our parents would probably take their car and head over to their sister’s in order to catch up and spend some family time together.

Instead, these days it’s more common to drop a message on WhatsApp, make a phone call or use a Facebook group, things that weren’t possible earlier on. This is not to say that people communicate or care more or less, but simply that the way they interact changed.

HTTP is no different: the semantics behind the protocol hasn’t changed much, while the technical implementation of how clients and servers talk to each other has been optimized over the years. If you look at an HTTP request from 1996 it will look very similar to the ones we saw in the previous article, even though the way those packets fly through the network is very different.

Overview

As we’ve seen before, HTTP follows a request/response model, where a client connected to the server issues a request, and the server replies back to it.

An HTTP message (either a request or a response) contains multiple parts:

- “first line”

- headers

- body

In a request, the first line indicates the verb used by the client, the path of the resource it wants as well as the version of the protocol it is going to use:

GET /players/lebron-james HTTP/1.1In this case, the client is trying to GET the resource at /players/lebron-james through version 1.1 of the protocol - nothing hard to understand.

After the first line, HTTP allows us to add metadata to the message through headers, which take the form of key-value pairs, separated by a colon:

GET /players/lebron-james HTTP/1.1Host: nba.comAccept: */*Coolness: 9000In this request, for example, the client has attached 3 additional headers to the request: Host, Accept and Coolness.

Wait, Coolness?!?!

Headers do not have to use specific, reserved names, but it’s generally recommended to rely on the ones standardized by the HTTP specification: the more you deviate from the standards, the less the other party in the exchange will understand you.

Cache-Control is, for example, a header used to define whether (and how) a response is cacheable: most proxies and reverse proxies understand it as they follow the HTTP specification to the letter. If you were to rename your Cache-Control header to Awesome-Cache-Control, proxies would have no idea on how to cache the response anymore, as they’re not built to follow the specification you just came up with.

Sometimes, though, it might make sense to include a “custom” header into the message, as you might want to add metadata that is not really part of the HTTP spec: a server could decide to include technical information in its response, so that the client can, at the same time, execute requests and get important information regarding the status of the server that’s replying back:

...X-Cpu-Usage: 40%X-Memory-Available: 1%...When using custom headers, it is always preferred to prefix them with a key so that they do not conflict with other headers that might become standard in the future: historically, this has worked well until everyone started to use “non-standard” X prefixes which, in turn, became the norm. The X-Forwarded-For and X-Forwarded-Proto headers are examples of custom headers that are widely used and understood by load balancers and proxies, even though they weren’t part of the HTTP standard.

If you need to add your own custom header, nowadays it’s generally better to use a vendored prefix, such as Acme-Custom-Header or A-Custom-Header.

After the headers, a request might contain a body, which is separated from the headers by a blank line:

POST /players/lebron-james/comments HTTP/1.1Host: nba.comAccept: */*Coolness: 9000Best Player EverOur request is complete: first line (location and protocol information), headers and body. Note that the body is completely optional and, in most cases, it’s only used when we want to send data to the server — that is why the example above uses the verb POST.

A response is not very different:

HTTP/1.1 200 OKContent-Type: application/jsonCache-Control: private, max-age=3600{"name": "Lebron James", "birthplace": "Akron, Ohio", ...}The first information the response advertises is the version of the protocol it uses, together with the status of this response. Headers follow suit and, if required, a line break followed by the body.

As mentioned, the protocol has undergone numerous revisions and has added features over time (new headers, status codes, etc), but the underlying structure hasn’t changed much (first line, headers, and body). What really changed is how client and servers are exchanging those messages — let’s take a closer look at that.

HTTP vs HTTPS vs H2

HTTP has seen 2 considerable semantic changes: HTTP/1.0 and HTTP/1.1.

“Where are HTTPS and HTTP2?”, you ask.

HTTPS and HTTP2 (abbreviated as H2) are more of technical changes, as they introduced new ways to deliver messages over the internet, without heavily affecting the semantics of the protocol.

HTTPS is a “secure” extension to HTTP and involves establishing a common secret between a client and a server, making sure we’re communicating with the right party and encrypting messages that are exchanged with the common secret (more on this later). While HTTPS was aimed at improving the security of the HTTP protocol, H2 was geared towards bringing light-speed to it.

H2 uses binary rather than plaintext messages, supports multiplexing, uses the HPACK algorithm to compress headers… …long story short, H2 is a performance boost to HTTP/1.1.

Websites owners were reluctant to switch to HTTPS since it involved additional round-trips between client and server (as mentioned, a common secret needs to be established between the 2 parties), thus slowing the user experience down: with H2, which is encrypted by default, there are no more excuses, as features such as multiplexing and server push make it perform better than plain HTTP/1.1.

HTTPS

HTTPS (HTTP Secure) aims to let clients and servers talk securely through TLS (Transport Layer Security), the successor to SSL (Secure Socket Layer).

The problem that TLS targets is fairly simple, and can be illustrated with one simple metaphor: your better half calls you in the middle of the day, while you’re in a meeting, and asks you to tell them the password of your online banking account, as they need to execute a bank transfer to ensure your son’s schooling fees are paid on time. It is critical that you communicate it right now, else you face the prospect of your kid being turned away from school the following morning.

You are now faced with 2 challenges:

- authentication: ensuring you’re really talking to your better half, as it could just be someone pretending to be them

- encryption: communicating the password without your coworkers being able to understand it and note it down

What do you do? This is exactly the problem that HTTPS tries to solve.

In order to verify who you’re talking to, HTTPS uses Public Key Certificates, which are nothing but certificates stating the identity behind a particular server: when you connect, via HTTPS, to an IP address, the server behind that address will present you its certificate for you to verify their identity. Going back to our analogy, this could simply be you asking your better half to spell their social security number. Once you verify the number is correct, you gain an additional level of trust.

This, though, does not prevent “attackers” from learning the victim’s social security number, stealing your soulmate’s smartphone and calling you. How do we verify the identity of the caller?

Rather than directly asking your better half to spell their social security number, you make a phone call to your mom instead (who happens to live right next door) and ask her to go to your apartment and make sure your better half is spelling their social security number. This adds an additional level of trust, as you do not consider your mom a threat, and rely on her to verify the identity of the caller.

In HTTPS terms your mom’s called a CA, short for Certificate Authority: a CA’s job is to verify the identity behind a particular server, and issue a certificate with its own digital signature: this means that, when I connect to a particular domain, I will not be presented a certificate generated by the domain’s owner (called self-signed certificate), but rather by the CA.

An authority’s job is to make sure they verify the identity behind a domain and issue a certificate accordingly: when you “order” a certificate (commonly known as SSL certificate, even though nowadays TLS is used instead - names really stick around!), the authority might give you a phone call or ask you to change a DNS setting in order to verify you’re in control of the domain in question. Once the verification process is completed, it will issue the certificate that you can then install on your webservers.

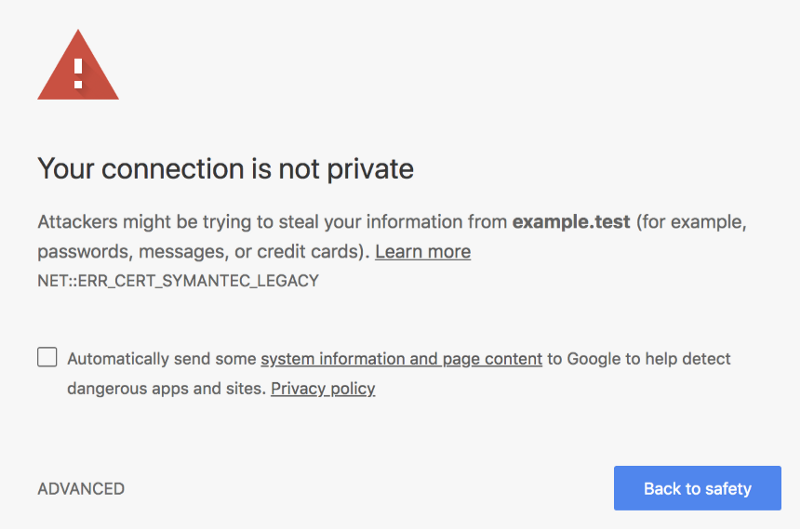

Clients like browsers will then connect to your servers and be presented with this certificate, so that they can verify it looks genuine: browsers have some sort of “relationship” with CAs, in the sense that they keep track of a list of trusted CAs in order to verify that the certificate is really trustworthy. If a certificate is not signed by a trusted authority, the browser will display a big, informative warning to the users:

We’re halfway through our road towards securing the communication between you and your better half: now that we’ve solved authentication (verifying the identity of the caller) we need to make sure we can communicate safely, without others eavesdropping in the process. As I mentioned, you’re right in the middle of a meeting and need to spell your online banking password. You need to find a way to encrypt your communication, so that only you and your soulmate will be able to understand your conversation.

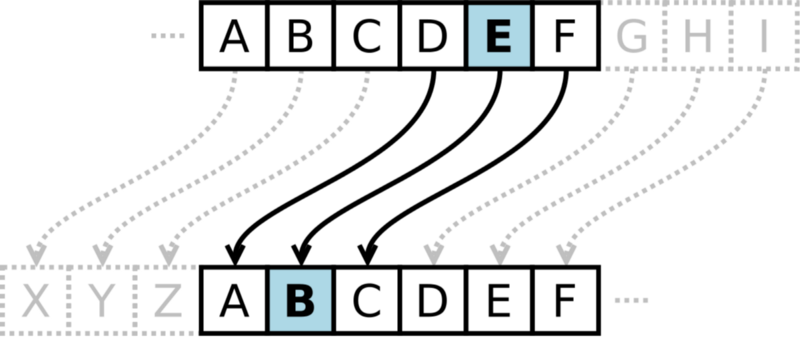

You can do this by establishing a shared secret between the two of you, and encrypt messages through that secret: you could, for example, decide to use a variation of Caesar cipher based on the date of your wedding.

This would work well if both parties have an established relationship, like yourself and your soulmate, as they can create a secret based on a shared memory no one else has knowledge of. Browsers and servers, though, cannot use the same kind of mechanism as they have no prior knowledge of each other.

Variations of the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol are used instead, which ensure parties without prior knowledge establish a shared secret without anyone else being able to “sniff” it. This involves using a bit of math, an exercise left to the reader.

Once the secret is established, a client and a server can communicate without having to fear that someone might intercept their messages. Even if attackers do so, they will not have the common secret that’s necessary to decrypt the messages.

For more information on HTTPS and Diffie-Hellman, I would recommend reading “How HTTPS secures connections” by Hartley Brody and “How does HTTPS actually work?” by Robert Heaton. In addition, “Nine Algorithms That Changed The Future” has an amazing chapter that explains Public-key encryption, and I warmly recommend it to Computer Science geeks interested in ingenious algorithms.

HTTPS everywhere

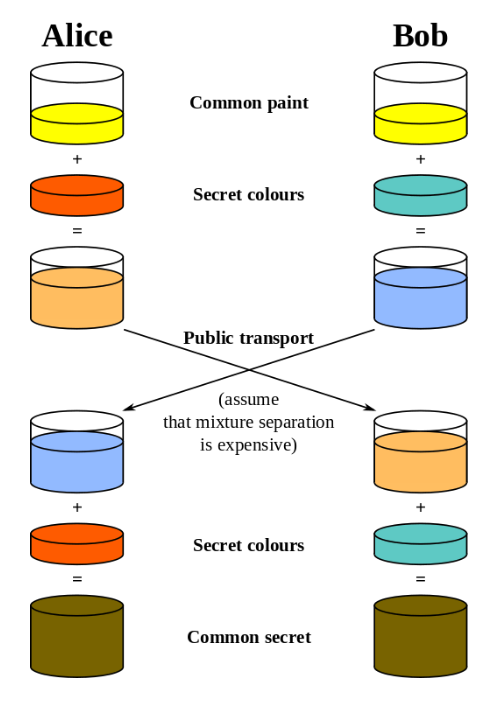

Still debating whether you should support HTTPS on your website? I don’t have good news for you: browsers have started pushing users away from websites not supporting HTTPS in order to “force” web developers towards providing a fully encrypted browsing experience.

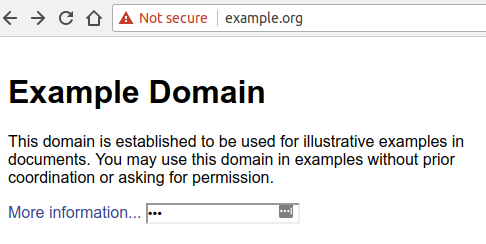

Behind the motto “HTTPS everywhere”, browsers started to take a stand against unencrypted connections - Google was the first browser vendor who gave web developers a deadline by announcing that starting with Chrome 68 (July 2018) it would mark HTTP websites as “not secure”:

Even more worrying for websites not taking advantage of HTTPS is the fact that, as soon as the user inputs anything on the webpage, the “Not secure” label turns red - a move that should encourage users to think twice before exchanging data with websites that don’t support HTTPS.

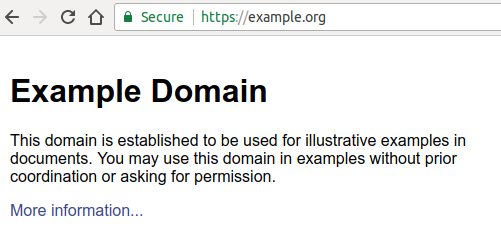

Compare this to how a website running on HTTPS and equipped with a valid certificate looks like:

In theory, a website does not have to be secure, but in practice, this scares users away - and rightfully so. Back in the day, when H2 was not a reality, it could have made sense to stick to unencrypted, plain HTTP traffic. Nowadays there’s almost no reason to do so. Join the HTTPS everywhere movement and help make the web a safer place for surfers.

GET vs POST

As we’ve seen earlier, an HTTP request starts with a peculiar first line:

First and foremost, a client tells the server what verbs it is using to perform the request: common HTTP verbs include GET, POST, PUT and DELETE, but the list could go on with less common (but still standard) verbs such as TRACE, OPTIONS, or HEAD.

In theory, no method is safer than others; in practice, it’s not that simple.

GET requests usually don’t carry a body, so parameters are included in the URL (ie. www.example.com/articles?article_id=1) whereas POST requests are generally used to send (“post”) data which is included in the body. Another difference is in the side effects that these verbs carry with them: GET is an idempotent verb, meaning no matter how many requests you will send, you will not change the state of the webserver. POST, instead, is not idempotent: for every request you send you might be changing the state of the server (think of, for example, POSTing a new payment — now you probably understand why sites ask you not to refresh the page when executing a transaction).

To illustrate an important difference between these methods we need to have a look at webservers’ logs, which you might already be familiar with:

192.168.99.1 - [192.168.99.1] - - [29/Jul/2018:00:39:47 +0000] "GET /?token=1234 HTTP/1.1" 200 525 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/65.0.3325.181 Safari/537.36" 404 0.002 [example-local] 172.17.0.8:9090 525 0.002 200192.168.99.1 - [192.168.99.1] - - [29/Jul/2018:00:40:47 +0000] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 525 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/65.0.3325.181 Safari/537.36" 393 0.004 [example-local] 172.17.0.8:9090 525 0.004 200192.168.99.1 - [192.168.99.1] - - [29/Jul/2018:00:41:34 +0000] "PUT /users HTTP/1.1" 201 23 "http://example.local/" "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/65.0.3325.181 Safari/537.36" 4878 0.016 [example-local] 172.17.0.8:9090 23 0.016 201As you see, webservers log the request path: this means that, if you include sensitive data in your URL, it will be leaked by the webserver and saved somewhere in your logs - your secrets are going to be somewhere in plaintext, something we need to absolutely avoid. Imagine an attacker being able to gain access to one of your old log files, which could contain credit card information, access tokens for your private services and so on: that would be a total disaster.

Webservers do not log HTTP headers or bodies, as the data to be saved would be too large - this is why sending information through the request body, rather than the URL, is generally safer. From here we can derive that POST (and similar, non-idempotent methods) is safer than GET, even though it’s more a matter of how data is sent when using a particular verb rather than a specific verb being intrinsically safer than others: if you were to include sensitive information in the body of a GET request, then you’d face no more problems than when using a POST, even though the approach would be considered unusual.

In HTTP headers we trust

In this article we looked at HTTP, its evolution and how its secure extension integrates authentication and encryption to let clients and servers communicate through a safe(r) channel: this is not all HTTP has to offer in terms of security.

As we’ll see in the next article, HTTP security headers offer a way to improve our application’s security posture, and the next post is dedicated to understanding how to take advantage of them.

Originally published at odino.org (22 August 2018).

You can follow me on Twitter - rants are welcome! ?