by Anthony Ng

What I learned from reading the Redux source code

I’ve always heard that reading code is a good way to expand your horizons as a developer.

So I made a conscious decision to really dig deep into a well-written JavaScript library and learn as much as I could.

I chose to look at Redux because it has a relatively small codebase.

This article won’t be a tutorial on Redux but rather tidbits that I learned by looking through their source code. If you’re interested in learning Redux itself, I highly recommend watching the Getting Started with Redux series from the creator of Redux himself, Dan Abramov.

Learning from Open Source

When new developers ask me what the best way of learning is, I respond that they should work on projects.

It’s amazing when you come across a project idea to work on that you would actually use yourself. That passion for a product will get you through those multi-hour debug sessions, and prevent you from abandoning it when the going gets rough.

But there’s a disadvantage in only working by yourself. You won’t notice any of the bad habits you pick up along the way. You won’t learn any best practices. You won’t hear about all of the new frameworks and tools that are sprouting around you. And you’ll quickly notice that your skills plateau during your lonely adventure.

Whenever possible, I recommend you seek out others developers to pair program with.

Sitting next to a peer (or if you’re lucky, someone more experienced) allows you to observe their thought processes. You get to see how their fingers glide over the keyboard. You get to watch how they struggle to tackle algorithms. You get to learn new developer tools and keyboard shortcuts. You get to soak in all the intangible things that you wouldn’t pick up working by yourself.

Being in the thick of the action is the ideal place to be.

Take for example the Stradivarius violin. Stradivarius instruments have a reputation for excellent sound quality that (arguably) have no equal. Many theories have been presented to explain the superiority of Stradivarius, ranging from wood being salvaged from old cathedrals to special wood preservatives that were used back in the day. People have tried to reproduce it with poor results because we don’t know how Antonio Stradivari worked.

But imagine all the secrets and tricks that could be learned if you were in the same room as Antonio, sitting right next to him as he worked.

This is how you should treat your pair programming sessions. You should bring a healthy dose of curiosity as you watch your peer create Stradivarius-esque code. There’s no better opportunity to see all the blood, sweat, and tears that go into a line of code.

For many, the opportunity to pair program is a rare luxury. But everyone can learn from others by looking at the code they’ve written.

Reading well-written code is like reading a well-written novel. It involves more interpretation on your part than if you were speaking directly with the author. But you can gather a wealth of information by reading through comments and code.

For those skeptical about how much can be learned by reading someone else’s code, take note of this story. A high school student named Bill Gates went dumpster diving in a company’s trash to get their source code and learn their secrets.

If someone like Bill Gates went through all that trouble to read someone’s code, I think it’s worth it for us to open up a Github repo and do the same.

Reading through code and learning from others is not a new concept. Tutorials are structured in a way that you follow a master through a coding journey. A well-written tutorial will feel like you’re sitting next to the writer. You get the opportunity to read about the problems they’re thinking about.

Hypertext links provide resources for you to read through and even do so in the middle of the tutorial (you wouldn’t do that in a peer programming session). The comment section and social media outlets allow you to have conversations with the masters.

I also watch people code on YouTube. I recommend the SuperCharged Live Coding Session series from the Google Chrome Developers’ YouTube Channel. You get to watch two Google engineers live-code a project. You get to see how they approach performance issues, struggle through typos like the rest of us, and get stuck.

Lessons I learned along the way

ESLint

Linting is a process of looking through your code for potential errors. It helps enforce code style and keeps your code consistent and clean. You can use your own custom style rules or use preset rules that follow conventional styles (such as one provided by Airbnb).

Linting is especially effective when working on a team of developers. It helps the code look like it was written by a single person. It also forces people to follow company style guides (that developers might not otherwise take the time to read).

Linters are for more than aesthetics. They force you to follow best practices. For example, they can tell you when to use the “const” keyword for variables that aren’t getting reassigned.

If you use React plugins, they can warn you about components that can be refactored into stateless functional components. They are also a great way of learning new ES6 syntax and even tell you where you can update your code with new features.

Here are instructions for quickly getting started with ESlint in your project:

- Install the ESlint package.

$ npm install --save-dev eslint2. Configure the ESlint options.

./node_modules/.bin/eslint --init3. Set up an npm script to run your linter in your package.json file (optional).

"scripts": { "lint": "./node_modules/.bin/eslint"}4. Run the linter.

$ npm run lintCheck out their documentation for more details on how to get started.

Many editors also have plugins that will lint your files as you type.

Sometimes linters might complain about code that you actually need, such as a console.log. You can tell your linter to ignore certain lines of code in their analysis.

To do this with ESlint, you can include the comments below:

// Single line Ignore console.log(‘Hello World’); // eslint-disable-line no-console// Multiline Ignore /* eslint-disable no-console */ console.log(‘Hello World’); console.log(‘Goodbye World’); /* eslint-enable no-console */Check for minification

I found a random “isCrushed()” function inside the source code that had no body to it. This was strange.

But I found that its only purpose was to see if the code was minified. During minification, function names and variables are shortened. There was an if statement that checked if the “isCrushed()” function still existed with that name. A warning would be shown if the minified code was used in development.

Don’t be afraid of errors

I had rarely used errors in my code outside of learning about it. JavaScript is a loosely-typed language so we should be paranoid about what gets passed into our functions. We should throw errors and scream like a strongly-typed language would.

Finally use try…catch…finally statements with these errors. Doing so will make your code easier to debug and reason with in the future.

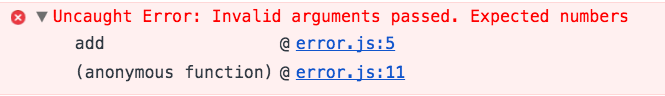

Take a look at that nice stack trace that errors produce in the console.

Errors makes your intentions explicit. For example, if your “add()” function only expects numbers, then let the whole world know.

function add(a, b) { if(typeof a !== ‘number’ || typeof b !== ‘number’) { throw new Error(‘Invalid arguments passed. Expected numbers’); } return a + b; }var sum = add(‘foo’, 2); // errors will prevent unintended consequences in your code Function Composition

There was a “compose()” function that built new functions out of existing ones:

function compose(…funcs) { if (funcs.length === 0) { return arg => arg } if (funcs.length === 1) { return funcs[0] } const last = funcs[funcs.length — 1] const rest = funcs.slice(0, -1) return (…args) => rest.reduceRight((composed, f) => f(composed), last(…args)) } If I have an existing function that squares a number and another function that doubles a number, I can combine them together into a new function.

function square(num) { return num * num; }function double(num) { return num * 2;}function squareThenDouble(num) { return compose(double, square)(num);}console.log(squareThenDouble(7)); // 98 I don’t know if I’ll ever use this, but it’s good to have this in my tools.

Native Methods

When I was looking at the “compose()” function, I ran into an Array method “reduceRight()” that I had never heard of. It made me wonder how many other native functions I haven’t learned.

Let’s look at a code snippet that uses the native Array method “filter()” and one that doesn’t, and see why it’s worth it to know what native functions exist.

function custom(array) { let newArray = []; for(var i = 0; i < array.length; i++) { if(array[i]) { newArray.push(array[i]); } } return newArray; } function native(array) { return array.filter((current) => current); } const myArray = [false, true, true, false, false]; console.log(custom(myArray)); console.log(native(myArray)); You can see how concise the code that uses “filter()” is. More importantly, we’re not reinventing the wheel. The “filter()” function has been used by millions of other users and is probably less buggy than your implementation.

Before writing your own solution, check to see if the problem has already been solved in the language you’re using. You’ll be surprised how many utility methods a language can have. (For example, check out this Ruby method for repeated permutations in an array).

Descriptive function names

Looking through the source code, I saw a number of long function names.

- getUndefinedStateErrorMessage

- getUnexpectedStateShapeWarningMessage

- assertReducerSanity

Although they don’t roll off the tongue, there is no confusion about what they do.

Use descriptive names in your code. You will spend more time reading code than writing it, so make it easier for you and everyone else to read.

The benefits of using long descriptive names far exceed the irritation you get from the extra keystrokes. Modern text editors have autocomplete features that help you type so you have no excuse to use “x” or “y” as variables.

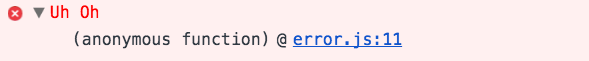

console.error vs. console.log

Don’t use console.log for everything. If you have an error that you want to print out, use console.error. You get a nice red print out with a stack trace in your console.

Take a look at the documentation for the console and see what other methods are available. There is a built in timer (console.time()), you can print out your info in a table layout (console.table()) and much more.

Don’t be afraid to dig through Open Source code. You’ll definitely learn something and might even find something to contribute.

Let me know what things you have learned by reading other people’s code.