by Jedidiah Yueh

Where to find top talent: the systems map of Silicon Valley

When I started my second software company, one of my venture capitalists asked if I really planned to build another technology company in a “wasteland” like Orange County.

A wasteland?

I had spent a fair amount of time in Silicon Valley. It looks quite a bit different than Newport Beach, Laguna Beach, or Corona del Mar — the beautiful beach cities of Orange County.

Instead of sprawling land and endless sunshine, you have broken roads meandering aimlessly through the dense, old neighborhoods of Cupertino, Menlo Park, Mountain View, and Palo Alto. Modern mansions of the tech elite sit a street away from dilapidated apartment buildings from the 1970s.

I grew up in Southern California, so it’s where I started my first software company, Avamar (acquired by EMC for $165 million). With a successful first outcome, it took less than a month to raise financing for my second software company, Delphix.

But I took a moment to reflect on my lessons from Avamar.

We pioneered an industry-changing technology, but we shipped product too late. We had a commanding two-year lead, but a Silicon Valley competitor ran us down. We had a hard time finding quality, experienced executives to fill key positions as we scaled, and could only hire from a small pool willing to relocate from afar.

In the end, we sold for $165 million, and our competitor sold for $2.4 billion.

It didn’t take me long to make a decision.

Location, location, location

I had to acknowledge the first rule of finding talent: location, location, location. In 2009, we moved Delphix to Silicon Valley where you can buy one-third the house for the price you’d pay in Newport Beach. But of course, there’s no beach.

The high cost of housing compresses disposable income. As a result, homes look a little more worn, cars motor around with dings and dents, and people look a little frumpy and disheveled. I call it the Tech Tax.

Strategically situated in the epicenter of technology, you have the privilege of buying $2 million teardowns on busy streets and the opportunity to gaze wonderingly at roving herds of tech talent.

But that talent can be mighty.

Once I plugged into Silicon Valley’s network, I met highly accomplished, articulate engineers who had founded or architected some of the biggest products in enterprise data management.

It’s like engineers grew on trees. I wanted to pick the talented as quickly as I could.

Lessons learned

I paid the price by suboptimizing engineering at Avamar. We didn’t just ship product a little late. We shipped product four years late. It took years for us to consume the quality tail — the quality required for a product to reliably support thousands of customers at varying degrees of scale.

In Orange County, there are few, if any, public software companies. We hired the best and brightest engineers we could find. Many worked as contractors for the government, building complex software programs like Ada compilers. I later realized that contractors often build themselves into their programs. By coding complex, hard-to-support solutions, you can guarantee job security.

That type of contractor-dependent engineering didn’t work in the world of enterprise software. We needed to ship software that just worked.

As my network widened, I met stronger and stronger engineers and decided we had to have the best at Delphix.

But engineers, like most people, don’t like to commute. And even inside Silicon Valley, location matters.

When we scouted locations for our first Delphix headquarters, another venture capitalists said to me, “Why don’t you put your offices in Redwood City, right next to Oracle’s headquarters? You can put up a sign that says, ‘Come Join the Next Oracle.’”

I wasn’t sure if he was joking or not.

To build a data management solution as sophisticated as ours, we needed engineers from some of the top database companies in the world, starting with Oracle. But we also needed great engineers who had solved problems in lower-level systems, such as volume managers and file systems.

A familiar layout

As I canvassed the valley, I came to a fascinating conclusion: Silicon Valley is geographically laid out like a systems map.

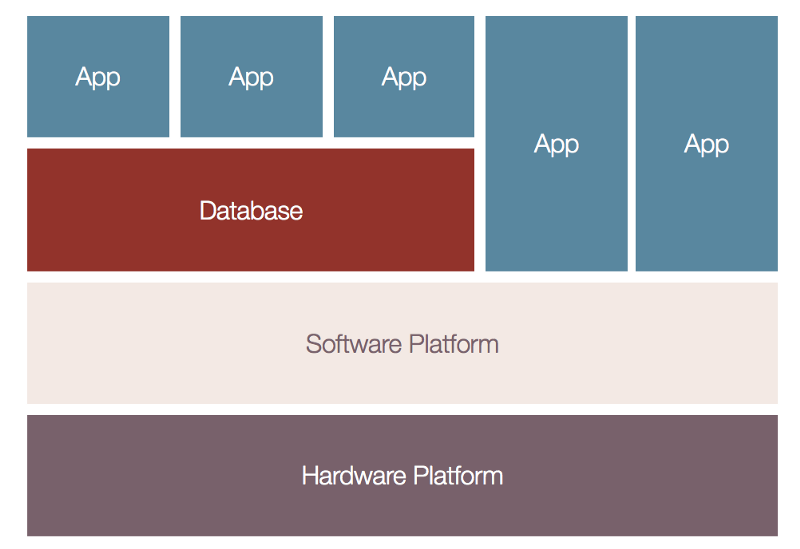

A basic application systems map looks like this:

At the bottom, you have hardware platforms, including items such as computer processors, network routers, and storage arrays. As you move up the stack, you have software platforms, such as Apple’s Mac OS or iOS operating systems, which mask the complexity of disparate hardware components.

One more level up, you have databases such as Oracle, the data engines that power today’s complex applications. And at the top of the stack, you have front-end apps that interact directly with end users, such as enterprise resource planning (ERP) solutions and the apps on your phone.

In the physical world of Silicon Valley, Highway 280 and Route 101 create an artificial island between San Francisco and San Jose. The first hardware giants such as Intel, HP, and Cisco emerged in the South Bay.

As the computer hardware industry matured, it gave rise to the next level in the systems stack: software platforms. As software platforms matured, they gave rise to the next level in the stack: databases. And as databases matured, they gave rise to more and more complex apps. Each layer unlocked the next over time.

San Francisco drew the new layers toward itself like a magnet, which resulted in a funny thing: Silicon Valley laid itself out like a systems map.

Hardware companies such as Intel, Cisco, and Apple sit at the bottom. Software platforms such as VMware, Facebook, and Google sit one layer above them. The world’s greatest database company, Oracle, comes next, between San Francisco and the South Bay.

And more and more app companies emerge in San Francisco every day, including Uber, Airbnb, and Twitter.

Moving forward with Delphix

After my analysis, we dropped Delphix in Palo Alto, right between Oracle and the hardware companies. And we drew our engineering and executive talent from both quarters.

Over the last decade, apps have become more and more leveraged, enabling the Ubers and Airbnbs to grow into awesome Appzillas seemingly overnight.

As a result, a major demographic shift has occurred. Talented young engineers want to work where all the hot app companies are headquartered. And they want to live in a big city.

Those twin draws have made San Francisco the new heart of Silicon Valley.

Talent comes first in engineering at Delphix, so we bowed to the laws of the valley and opened a second office in the city.

The result? We shipped product by the end of the same year we moved. In December 2009, Staples became our very first customer. After that, we added brand name after brand name, over 30% of the Fortune 100. And we have some of the highest customer satisfaction and retention rates in the industry.

If you need to hire the world’s top software engineers, they’re probably in the California Bay Area. They can help you build your rocket ship.

Just make sure you’re looking for them in the exact right place.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this article, please hold down the clap button below ? to help others find it. The longer you hold it, the more claps you give!

About Me

I’ve spent two decades decoding innovation, collecting the hidden frameworks that drive many of the most successful entrepreneurs in technology today. I’ve personally implemented these frameworks, inventing software products at Delphix and Avamar that have driven more than $4 billion in sales. Disrupt or Die (available on Amazon) is my first book.

Parts of this article are excerpted from Disrupt or Die.

Sign up below to get periodic updates, notes on innovation, and a little frivolity along the way. You’ll also get the first five chapters of my book free.